On a clear morning in the early summer of 1962, students of the Mevo’ot elementary school in Beer Tuvia went poppy picking. At the end of meter-high stems, huge flowers — almost as big as a saucepan — opened up. When the petals fell, they revealed the fruit: a pod resembling a small pomegranate. The dried pod could be shaken like a rattle, and the countless dark blue seeds would rustle inside. These seeds, with their sophisticated sweetness — as if a nut fell in love with cardamom and the couple shared a sip of delicate liquor — were growing on Karmiel family’s farm. The poppies the students picked that day helped raise money for children sick with Polio. They earned 90 Israeli Lira (about $300 today).

For several years, the Karmiel family enjoyed respectable earnings around Purim — poppies’ flowering season extends between March and June. But one day it all ended.

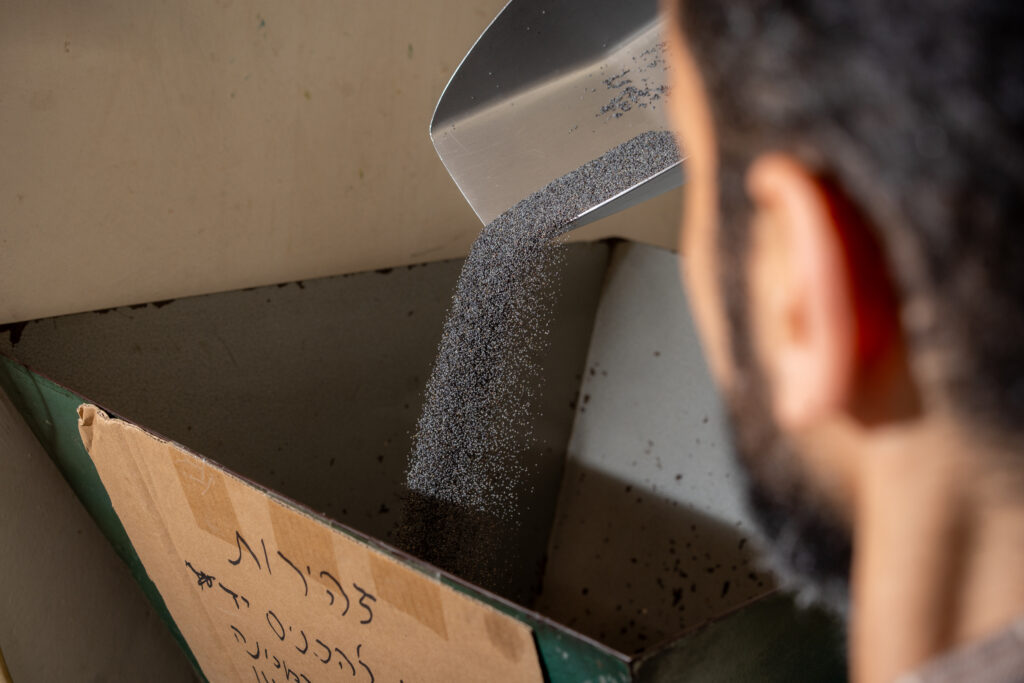

Poppies produce edible seeds, they also produce something else. When one scratches the stems or the seed capsule, they release a white, analgesic and intoxicating resin: opium, “plant juice” in ancient Greece, which is to make heroin. International treaties have limited the commercial growing of poppies to a small number of countries — the Czech Republic and Turkey grow about half of the world’s poppy seeds and legal opium. In Israel, farms growing poppies began to close and the Karmiel family’s farm was one of them.

I heard this story from their granddaughter Nitzan Yarden-Susid, who has worked as a pastry chef and culinary guide for the last 25 years. I study bread baking with her at the Attilio culinary school. Yarden-Susid says she feels bad about losing the family’s field, “but even more, about poppy seeds. They’re no longer trendy. For most people, they’re just the old-fashioned filling for hamantaschen, the boring version, before chains like Roladin appeared with more innovative variations.”

Yet retailers are, in part, to blame for this dull image. “When you buy a bag of ground poppy seeds, it’s already bitter. Seeds are fatty, and fat goes stale. Freshly ground poppy seeds have this lightly bitter aftertaste, which makes you want more and more. People aren’t familiar with it, and it’s a shame, because you can add poppy seeds to many things. I just love poppy seeds,” she adds.

So are poppy seeds that rather bland, boring flavor we all know, in the rather dull texture — the Shtetel’s chocolate? Or is it an exquisite delicacy, and the problem is that we take it for granted and so deny our palate a supreme pleasure?

An Exclusive Club

Dwellers of the Mediterranean Basin have been eating poppy seeds and smoking opium since the Stone Age. Traces of opium were discovered in pottery vessels from the time of the Judges. Around 2400 years ago, Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, recommended a poppy seed remedy for convalescence. It was a paste of cooked, crushed poppy seeds with honey. If only he had thought to wrap it in some nice cookie dough. Galen, his follower, recommended sprinkling poppy seeds on bread before baking. Poppy seeds have always been here, and they have always been the same.

It makes sense, because poppy seeds are one of the few spices Europe contributed to the world. The most famous members of this exclusive club are celery seeds, mustard seeds, and anise seeds. Most spices originated in tropical climates, where plants developed chemical weapons to dispel parasites and pests. Mustard plants use sulfur to burn any larva that dares sink its teeth into the plant. Rosemary fights bugs and viruses with an acid cocktail, which accounts for its scent. Poppies put their enemies to eternal sleep.

For us, these lethal traps are nothing but a pleasant tease to the tongue and nose. And perhaps the infinitesimal residue of opium in poppy seeds is the reason for the aftertaste Yarden-Susid described, that light bitterness that makes us come back for more. It might be that the opium accounts for that final scent our nose captures when we eat fresh poppy seeds — a light, cool, slightly medicinal vapor. Or perhaps those opium residues simply amplify our pleasure, separately from any particular flavor, create that “mmm!” feeling we get when eating freshly ground poppy seeds.

The Purim Connection

In the Middle Ages, poppy seeds met their other half, never to part from: dumplings.

Dumplings have not been here since forever. They came from the Steppes of Asia. They were the “to go” food of the traders of the Silk Road, the lunch box of the Mongols. Ancient, dry remains of gyozas and sambusak have been unearthed in barrows all along historic trade routes. The most ancient of them, about 1500 years old, was discovered in Xinjiang in the west of China, the land of the Uyghurs, right in the center of Asia.

In Medieval Europe they had names like pierogi and manti and ravioli, and in Germanic lands they were called taschen. Germanic people loved their taschen. They had meat-filled fleischtaschen and vegetable-filled gemüsetaschen, potato-filled kartoffeltaschen, käsetaschen with cheese, and lachstaschen with salmon. And on the sweet side, they had a selection of nusstaschen with nuts, kirschtaschen with cherries and in winter, mohntaschen, filled with mohn, which is German for poppy seeds.

Mohntaschen met Jews, and poppy seeds became the official flavor of Purim. When it comes to Ashkenazi food, it’s the same old story. Noted Ashkenazi culinary expert, Shmil Holland, recounted it in 2016, in an article he wrote for the book “Polish”: All through the Middle Ages and the early modern era, our forefathers munched on converted versions of goyishe recipes, and “when decrees and expulsions forced them to grab their traveling stick, they took their food with them.”

The relationship between the German mohntaschen and Purim was incidental: these pastries were prevalent and cheap, because poppy seeds were in season; due to their compact form, they could be one of the items in a mishloach manot, which should contain various sweet foods. (They were a better choice than mohnstrudel (poppy seed cake), mohnnudeln (sweet, poppy seed covered gnocchi-like noodles) and mohnklöße (poppy seed-rich bread pudding).) And the best part was the name — hamantaschen (tasche is the singular, taschen the plural form), Haman pockets. “And it’s not a distortion of mohntasche, hamantaschen is the original name,” says Holland, who asked me to call him as soon as he learned I was writing about poppy seeds. “In German, when you ask for one pastry, you say, give me hamantasche, the h is like the a in ‘a dumpling.'”

“That’s the only relation to Purim, by the way,” he says. “The symbolism, poppy seeds as the king’s treasure, a hidden miracle — these are all late exegeses from the Hassidic literature. Up to the 19th century it was a common pastry, and then there’s the word play, which is nice to have on holidays, and that’s all. This is especially true for Haman’s ‘plucked ears’. Hamantaschen have nothing to do with ears. There are other cookies that are called Haman’s ears or oznei haman, but they are an ancient Italian Purim food, a cookie made from fried dough, like palmiers. The common pastry was hamantaschen, and in the early 20th century, the Hebrew Language Committee gave them this name, from Medieval literature, quite arbitrarily.”

I located the original, Italian Purim pastry in a text considered to be the first Hebrew play, “A Comedy of Betrothal” (צחות בדיחותא דקידושין), written in the 16th century. The play refers to the mitzvah of eating oznei Haman, described as “cakes of semolina mixed in oil.” Some mentions are even older. In the 14th century biblical exegete Joseph Ibn Kaspi, and later Isaac Abarbanel, wrote about a “wafer cooked in oil” that resembles “cooked ears.”

The last mention I could find were in Muli Bar David’s 1964 “Sefer Bishul Folklori” (A Folklore Cookbook), where oznei Haman are “twisted, crunchy cookies” and in the lifestyle column of the newspaper HaYom in 1966, where young journalist Judy Winkler shares a recipe for oznei Haman that are fried squares of pasta dough kneaded with baking powder. When deep fried, the baking powder creates bubbles in the texture of the solidifying cookies. Winkler, who had survived the Holocaust as a child, dedicated much of her long journalistic career to writing about the past and preserving it.

Like poppy seeds perhaps, those sweets were pushed aside by the endless variety of flavors that reached Europe with globalization. Because who can beat tropical flavors, and of course, the world-favorite chocolate?

“Poppy Seeds Make Chocolate Eat Dust”

“I feel like stepping into the kitchen and giving [poppy seed paste] a try to see where I can take it,” says Yarden-Susid. “Poppy seeds can beat chocolate. They’re so special, and chocolate can feel too heavy at some point. You can always add sweetness, but I wonder if we should. The bitter ending and delicate flavor are terrific. Then we have the grainy texture. The smooth creaminess of Nutella and its duplicates is an important factor, so we should be thinking about texture. There are industrial poppy seed pastes, and I suppose they taste terrible, because freshness is so crucial here. I’m all in. I have something to work on.”

“Poppy seeds make chocolate and marzipan and everything else eats dust. It’s the tastiest filling,” adds Holland. “It’s just a matter of perception. When it comes to pastries, we immediately think of French baking, but Viennese and Central-European baking is a heritage in itself. In some Michelin restaurants they serve pressburger, a world-famous poppy seed roll which is a classic. If we want to go back to poppy seeds, we should simply be mindful of quality, that the poppy seed mixture tastes right and is not too dry, that it is cooked in plenty of milk and butter. Upgrading poppy seeds means restoring past glory.”

Holland and Yarden-Susid point out another challenge: there are two groups of people, they said, poppy seed-lovers and those who just can’t stand this flavor. True, it’s not a flavor for everyone. “De gustibus non est disputandum,” there’s no point in arguing about taste… The ones that love poppy seeds are clearly right.