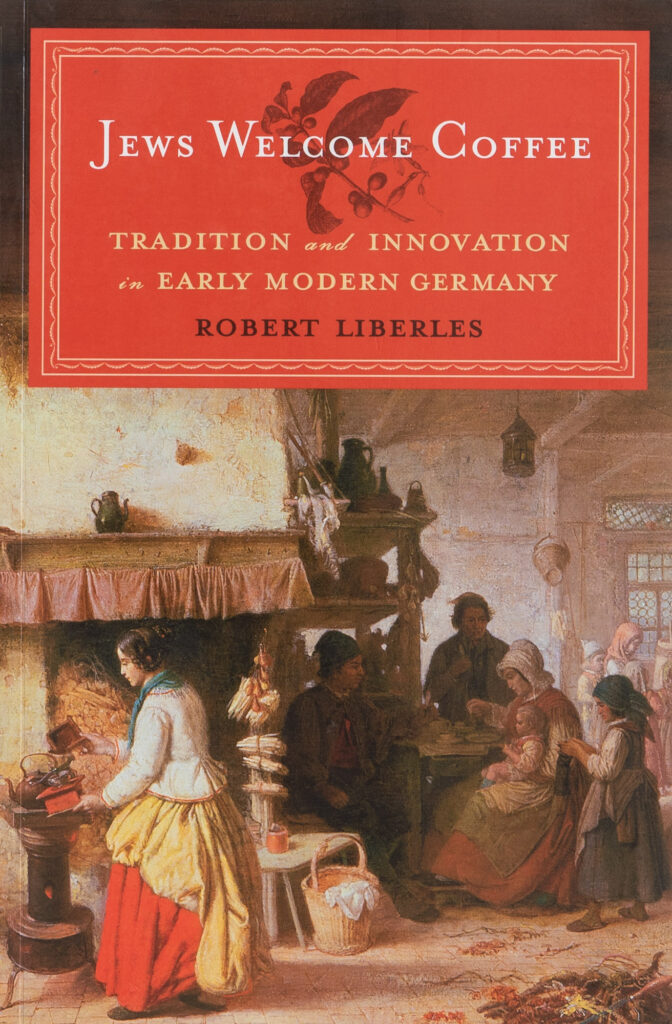

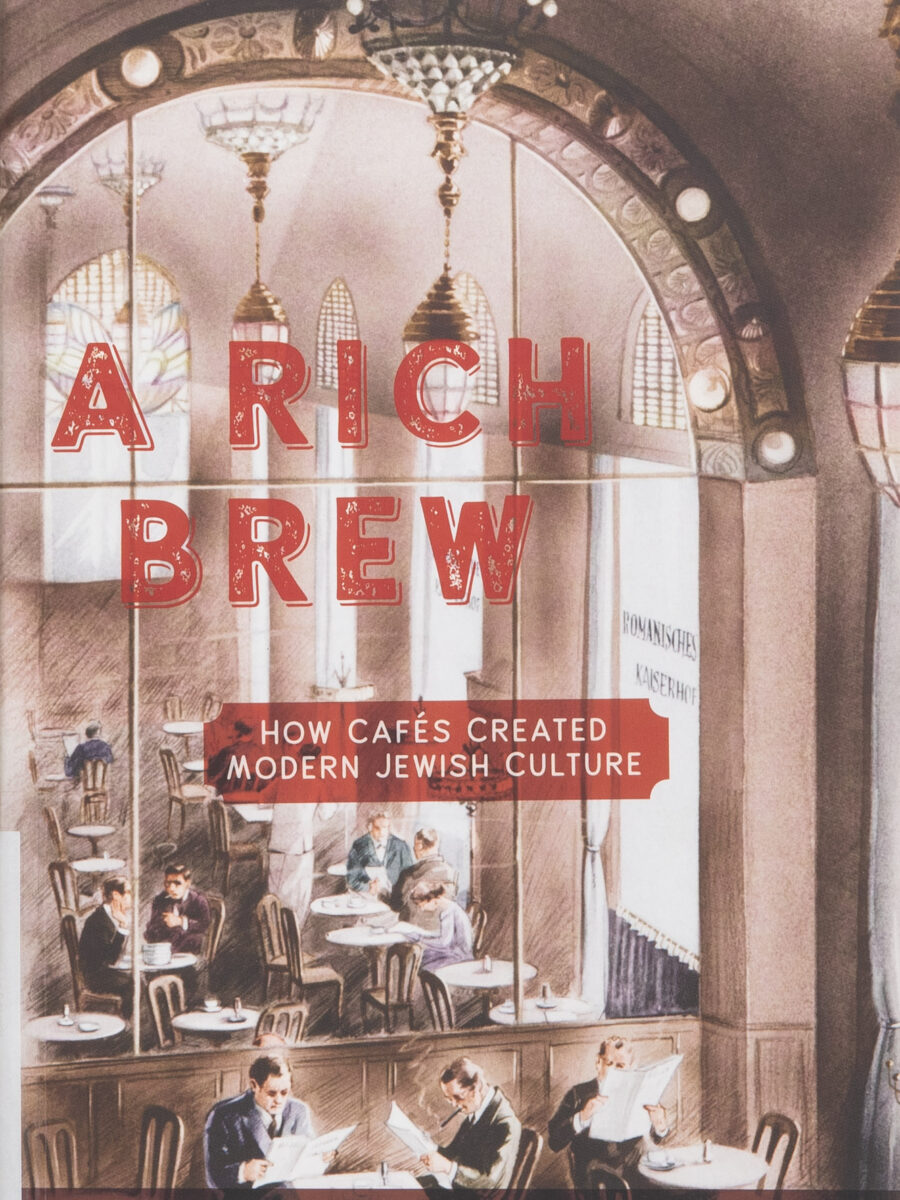

Jews Welcome Coffee: Tradition and Innovation in Early Modern Germany

Could an 18th century Jew visit a coffee house on shabbat? Historian Robert Liberles investigates this, and many other questions, in his book about Ashkenazi German history. Jews Welcome Coffee presents a new view of German Jews from the mid 17th to mid 18th centuries through the lens of coffee. It examines the role of coffeehouses in daily life and rabbinic discussion, and the clandestine coffee roasters of the ghetto. Importantantly, Liberles’ approach uncovers new stories of lower class Jewish citizens and interactions between Jews and Gentiles otherwise forgotten by history.

Noa Berger’s recommendation of “Jews Welcome Coffee”

The charm of this book lies in demonstrating how an apparently esoteric topic opens a window to wide and profound historic, economic and cultural questions. Liverles, a professor of Jewish history at Ben Gurion University, who passed away the same year the book was published, wrote a book about a very specific topic: the economic and cultural history of coffee trade and consumption in Jewish communities in Germany of the early modern period.

Despite the particular, some would even say esoteric, nature of the topic, Liverles successfully ties the question of “Jews and coffee” to the changes occurring in Jewish communities at the time, and to wider transformations in European society. Through the prism of coffee, he demonstrates the complicated position of Jewish communities in Europe, and their use of this new product, and the new spaces for its consumption (cafés), as a way of enriching community life and establishing trade relations, as the authorities were trying to prevent their economic and social assimilation.

To me, the principal force and contribution of this book is in the message it conveys about research and writing – about coffee, food and everything else. Jews Welcome Coffee is brimming with fascinating anecdotes; from the rabbinical pilpulim (casuistry) leading to the invention of botz coffee (“mud”; black coffee brewed in boiling water, as opposed to being cooked) as a creative solution for coffee drinking on Shabbat, to the surprising story of the female orthodox coffee traders. At the same time, Liverles avoids, as he himself states in the book’s introduction, the “romanticization” of coffee, so frequent not only among its amateurs, but also among researchers recounting the beverage’s history.

Unlike many others, Liverles makes no claims regarding the power of coffee to upturn the world, nor does he suggest that Jews were the sole responsible for its success and distribution. However, he does propose coffee – and cafés – as an “almost perfect” symbol of the profound changes, revolutions and transformations of the times: “coffee was not the reason for the revolutions, but it very possibly was what the revolutionaries drank”.

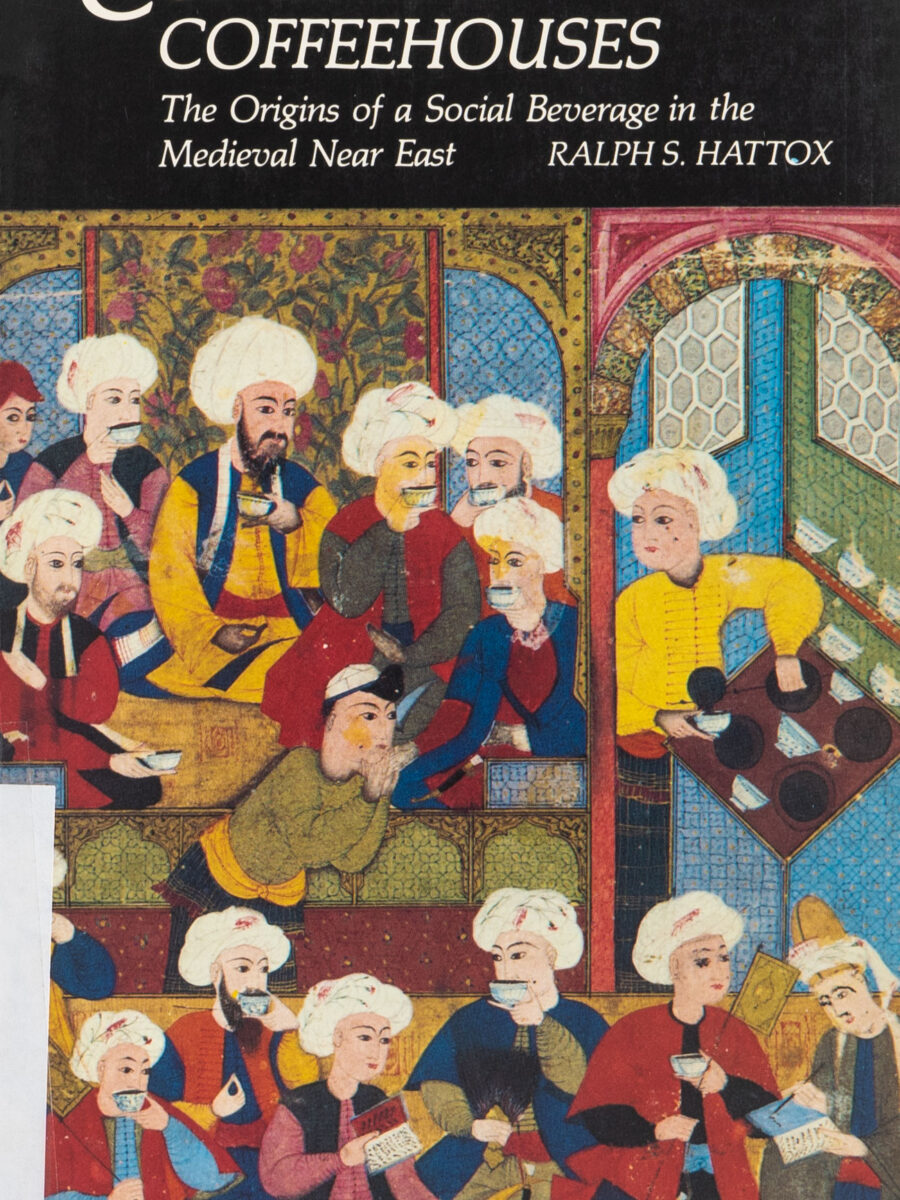

Another insight I drew from the book is the reminder that the production and distribution of coffee span half of the planet and about a thousand years (at least), and that the beverage’s receptance, rejection or influence were closely tied to the social and economic structure of the places of its production and consumption. Liverlis shows, for example, that Germany was unique in its opposition not only to the café, which posed a threat to authorities from Yemen to France as a place of assembly and gossip, but also to the beverage itself. Instead of offering culture-based explanations (coffee was initially perceived as a “Turkish” beverage, black and exotic), he links this opposition to economic interests of the monopolistic German beer industry, and to the fact that Germany did not have coffee-producing colonies (as opposed to Portugal, France and the Netherlands).

Jews Welcome Coffee is a persuasive account of the power of coffee, and of food in general: it is simultaneously linked to the anecdotal, the momentary, the entertaining and the esoteric, but also to major and extensive social and economic processes.

Book details

- author

- Robert Liberles

- publisher

- Brandeis University Press

- Year published

- 2012

- Pages

- 169