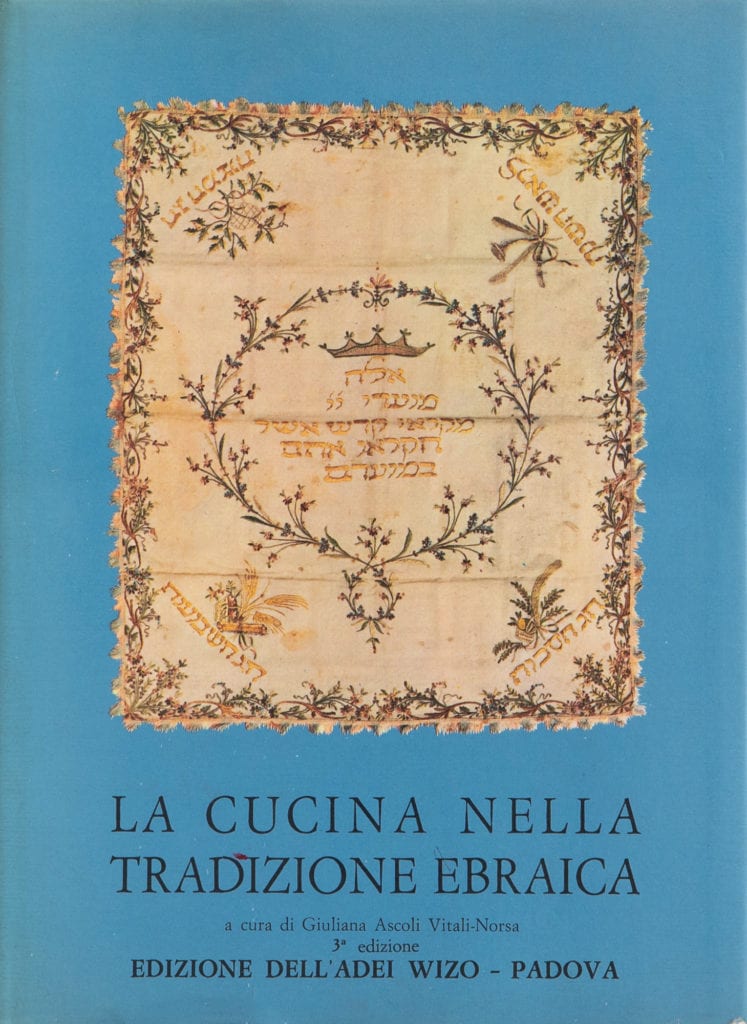

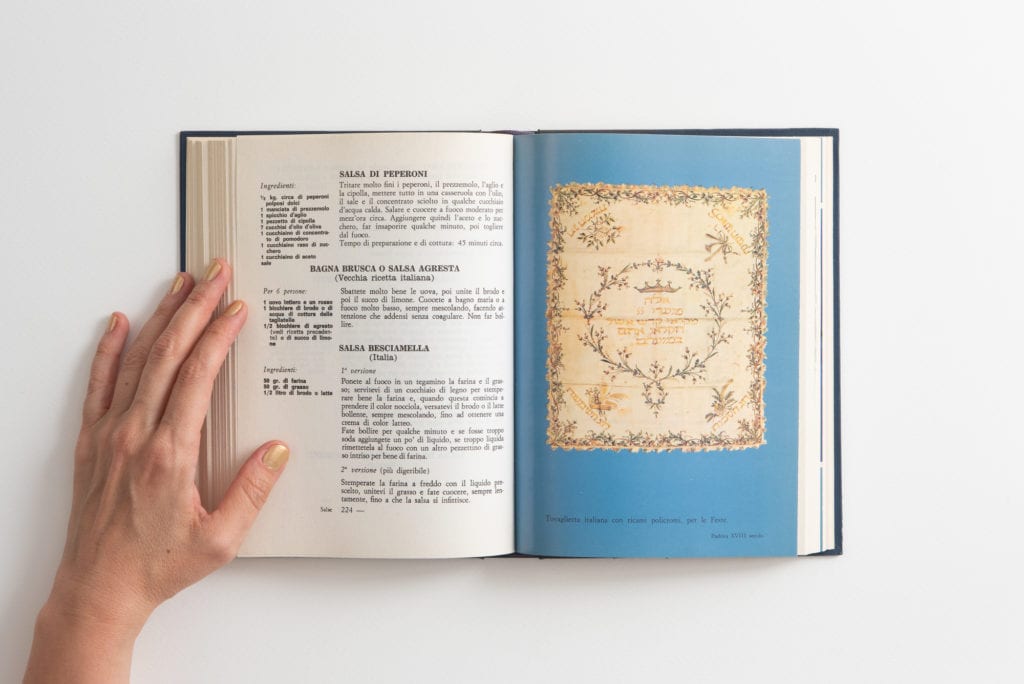

La Cucina Nella Tradizione Ebraica

This book brings together 700 recipes collected by Adei Wizo, the Association of Jewish Italian women of Padua, and Giuliana Ascoli Vitali-Norsa. According to culinary anthropologist and cookbook author Claudia Roden: “It is an important book, and the first, I believe, that covers in a broad way the cooking of the Jews whose presence in the Italian peninsula was uninterrupted for two thousand years.” The recipes, which vary greatly by locale, come from historic Jewish communities in Rome, Venice, Padua, Livorno, Piedmont, Tuscany and beyond. There are also Ashkenazi and Sephardi recipes that came to Italy with Jews escaping persecution centuries ago. As Roden adds: “they all have an Italian touch…. It is uncanny how much they tell us about the Jewish past in Italy.”

Claudia Roden’s recommendation of ‘La Cucina Nella Tradizione Ebraica,’ as told to Gabriella Gershenson

According to the dust jacket, “the Adei Wizo of Padova collected 700 Jewish recipes from all over Italy.” Adei Wizo stands for “the Association of Italian Jewish Women,” and Giuliana Ascoli Vitali-Norsa was in charge of collecting and editing the recipes. They come from families and have been handed down from one generation to another. I tried many. Some are holiday or Shabbat dishes. Most are very simple, some are complex, grand and sophisticated. They are delicious.

It is an important book, and the first, I believe, that covers in a broad way the cooking of the Jews whose presence in the Italian peninsula was uninterrupted for two thousand years. The old historic communities that were once dispersed throughout the peninsula have disappeared or lost their identities. Jews now live mainly in Milan, Turin, and Rome. The old family dishes are among the few things that remain as a testimony to their past.

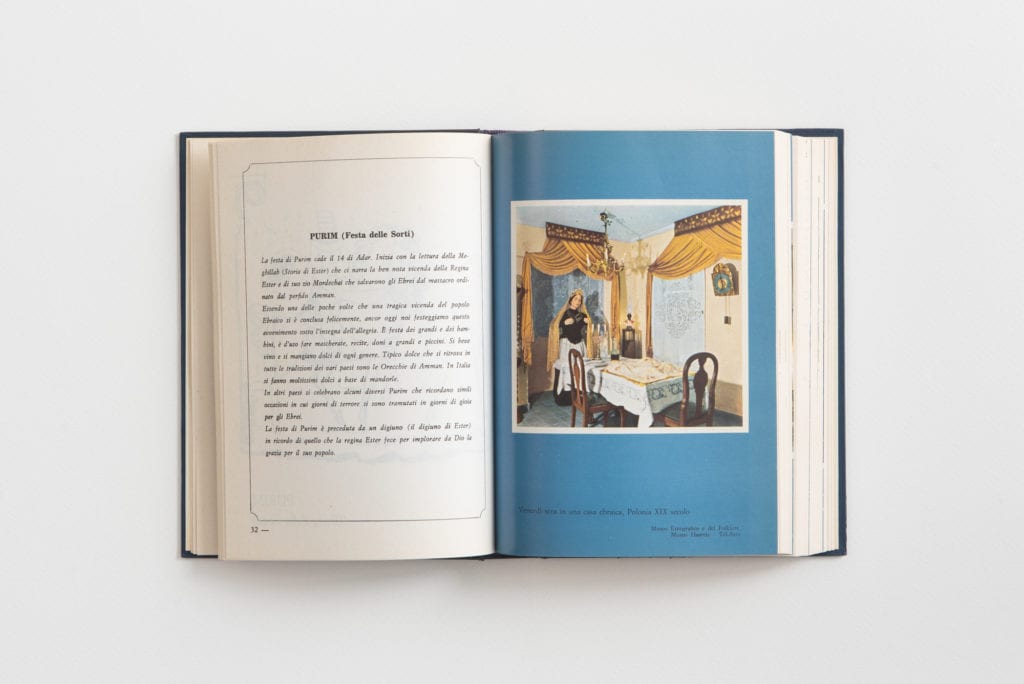

The cooking of Italy is very regionally diverse because until its unification in 1870, it was divided into many separate states. The cooking of the Jews is diverse in a different way, reflecting the individual and varied histories of the once numerous Jewish communities. These are represented in the book as antica or vecchia ricetta: Romana, Veneziana, Padovana, Ferarese, Anconetana, Marchigiana, Fiorentina, Toscana, Piemontese, Triestina, Livornese. Some are marked simply as Italian. Some have a name attached to it, like Rachele, Rebecca, Rosa, nona Sara, Ezechielle. There are Ashkenazi recipes from Germany, Poland and Russia, and Sephardi recipes that are Spanish and Portuguese, and recipes from Turkey, Tunisia and Libya, but they all have an Italian touch and must have come from long-established local communities. It is uncanny how much they tell us about the Jewish past in Italy.

The earliest and largest colonies of Jews existed in the South — in the little ports around the Gulf of Naples, in Puglia, Basilicata, Calabria, Sardinia and most particularly in Sicily, until the Inquisition banished them in the beginning of the 16th century from that part of the Italian Peninsula that was under Spanish rule. The foods they took with them when they fled to central and northern cities — vegetables like aubergines and artichokes, garnishes of raisins and pine nuts and of anchovies and capers, marzipan pastries, sweet-and-sour flavors, and the custom of deep-frying battered morsels in oil, most of which came to Sicily with the Arabs — are still associated with the Jews. Many dishes labelled “alla giudea” or “alla ebraica” throughout Italy and in the book are like those of the Italian South.

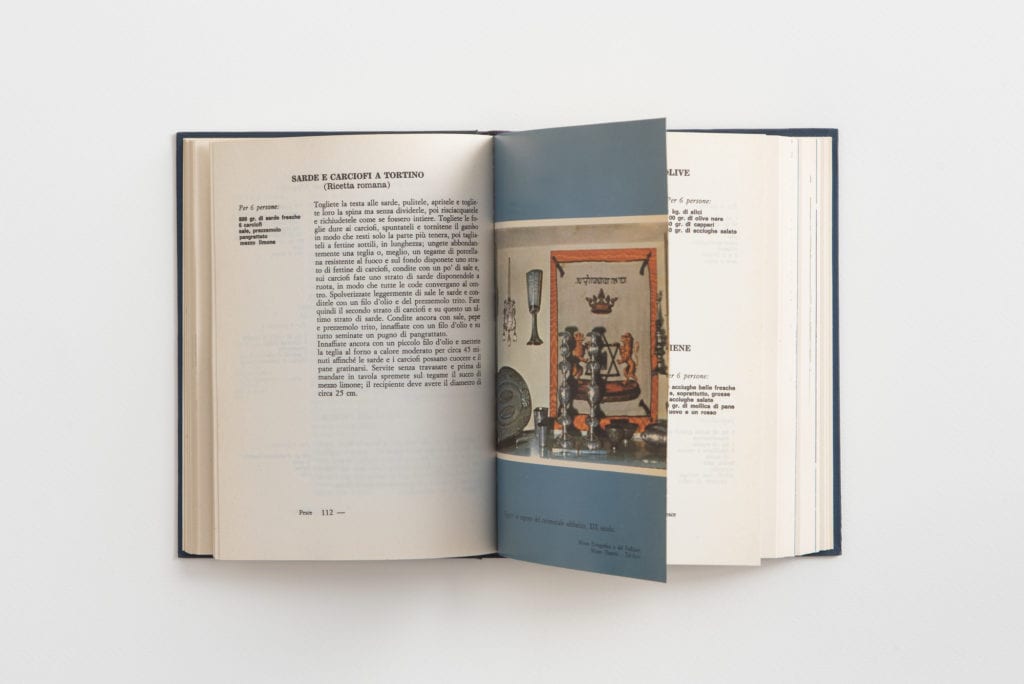

Many of the Roman dishes in the book, like ceci coi pennerelli (chickpeas with bits of meat from the knuckle) and aliciotti con l’indivia (anchovies with chicory), caponata alla giudea with aubergines (eggplants), concia di zucchine (fried and marinated courgettes) and cassola, the creamy ricotta cake, are a testimony of the swamping of the Roman community by refugees from Sicily and the South.

The massive migration of Jews from the South and their arrival in cities of central and northern Italy coincided with the arrival there of a flow of escapees from German lands at the same time as thousands of refugees arrived from Spain and Portugal. The crisis that this huge influx created resulted in their segregation in special quarters and the imposition of restrictions. Venice was the first city in 1516 to force Jews to live in a special quarter behind walls where they were locked in at night. (The quarter was called ghetto after the hard “G” Jewish pronunciation of the Venetian word for “foundry,” because it was situated near an old foundry.) In most Italian cities where they lived, the Jews were confined in ghettos for up to three hundred years, until Napoleon’s armies occupied Italy in 1796 and tore down their gates. The Jewish cooking of the communities in the different Italian cities reflected the origins of the inhabitants of the ghettos.

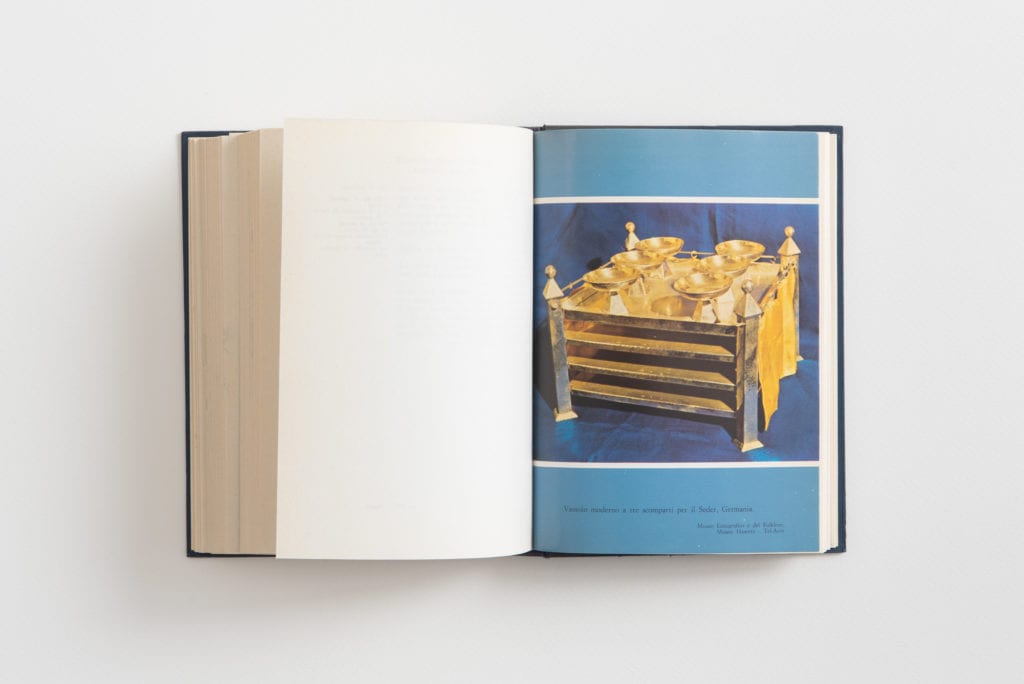

In Venice, Portuguese Marranos (Christianized Jews) and Turkish and Levantine merchants co-existed with German Jews and those from Sicily. The Levantini brought riso pilaf and risi colle uvette (rice with raisins eaten cold). The Sicilians brought rice with artichokes. The Levantini introduced the spices and aromatics they dealt in. The Arab combination of pine nuts and raisins came both with the Sicilians and the Levantinis. The Iberians introduced salt cod dishes, frittatas and almond-y sweets, orange cakes and flans. The tedeschis (Germans) introduced goose and duck, beef sausages and goose salame, pesce in gelatina (jellied fish) and polpettine di pesce (gefilte fish), penini de vedelo in gelatina (calf’s foot jelly) and kneidlach, which became cugoli, all of which are in this book.

An example of the interweaving of cultures in Venice and elsewhere is pastizzo di polenta with raisins and pine nuts. Another is the boricche—little pies halfway between Portuguese empanadas and Turkish boreks, but with fillings unique to Italy, such as fish with hard boiled egg, anchovies and capers, fried aubergines and tomatoes, or with pumpkin, crushed amaretti and chopped crystallized citrus peel.

Continuous persecutions in Germany and the Rhinelands had sent waves of refugees from as early as the thirteenth century across the Alps, spreading throughout Lombardy and the Veneto. They represent the origin of the majority of communities of northern Italy. The cooking of those of Trentino and Alto Adige was very German with stuffed goose, potato cakes, cabbage, dumplings and apple fritters.

In Piedmont, a large part of the communities were made up of an influx of Jews expelled from Provence, and the cooking had a strong French accent. Take polpetone, a galantine of turkey or chicken with minced veal and pistachios. Other Provençal dishes that have come into the Jewish tradition are patate e pomodori of Ferrara, which is like a tian with baked layers of potatoes and tomatoes, and the curious Tuscan sweet spinach tart, torta di mandorle e spinaci, which is a speciality of Nice.

In Trieste, the varied mix of dishes like gulyas (goulash) and paracinche (stuffed pancakes) of Hungarian origin, the yeast cake potizza of Austrian descent and the Yugoslav bean soup called jota are reminders that Austria annexed the city when it was part of the Habsburg empire, and many flooded into the city from all over the empire.

Moneylending, forbidden by the church, was a Jewish profession because Christian guilds pushed them out of other spheres. Jews were invited into many cities where they financed economic expansion, and the local nobility often became their protectors. Thousands settled in cities such as Ferrara and Modena, Verona, Padua and Mantua, Florence, Pisa, Luca and Sienna. Many sophisticated old Jewish recipes like buricche ferraresi (little pies filled with chicken), arancini canditi padovani (balls of orange paste) and tortelli di zucca mantovani (pumpkin tortelli) are linked to these cities where Jewish life flourished and where cooking reached a high level of sophistication.

Sephardim and Marranos from Spain and Portugal spread all over the country. Their commerce in maritime exchange was the dominant force in port cities like Ancona, Livorno and Venice. Some had their own ships. They traded with their relatives and coreligionists around the Mediterranean, including their New Christian connections in Spain and Portugal and importantly, the Americas. The Marranos were among the first to bring tomatoes and pumpkins to Italy. Many of their dishes have tomatoes, like fish alla mosaica (mosaica means Moses). Of course, soon after, tomatoes were the biggest thing in the whole of Italy, but these merchants were the first to bring it.

The most glorious Jewish community was that of Livorno. In 1593, the Grand Duke Ferdinando I de Medici turned the city into a free port and invited in merchants of all nations, and Jews in particular. Portuguese Marranos flooded in and it is they who shaped the character of the community and the style of cooking. Portuguese delicacies like uova filate or filli d’oro (threads of egg yolk cooked in syrup) and Monte Sinai and bocca di dama made with eggs and almonds are among their legacies. A number of Livornese chocolate cakes owe their existence to contacts with Marranos in Bayonne and Amsterdam, where Jews started the first chocolate factories with cocoa sent by New Christians in South America. The many North African dishes like couscous, polpete moksci (meatballs with vegetables stuck in) and makroud, a cake with dates, are part of an intriguing story. Ships bringing Marranos from Portugal were regularly intercepted by pirates in the Mediterranean, hostages were brought to Morocco and Tunisia, and Livorno grandees came to pay their ransom, until the grandees were invited to stay and offered high positions. They joined the local communities but remained separate and formed their own community that remained connected with Livorno, and some of the foods there still reflect this exchange.

You might think this cookbook is odd because it has German recipes and Polish ones, yet they are Italian because they’ve been part of the cuisine for so long. We have to treasure those recipes because people are cooking them. Each of them has a story that reminds us of a very special and unique Jewish past.

Book details

- author

- Giuliana Ascoli Vitali-Norsa

- publisher

- Edizione dell’Adei Wizo

- Year published

- 1979

- Pages

- 432