The term “workers’ restaurant” denotes, first and foremost, a socio-economic distinction: culinary institutions for those who live off hard physical labor. These workers rely on hearty and nutritious dishes at low prices to fuel their work. In Israel of today, most citizens belong to the middle class, and most of these workers are Palestinians (some of them Israeli citizens, and most of them residents of the occupied territories) and foreign workers (documented and undocumented). Only a small percentage of Jewish Israelis work in fields like construction and farming, but this was not always the case. Here, I trace an arc from the cooperative restaurants that fed early Zionists to the dining rooms of Google and restaurants next to Tel Aviv’s Central Bus Station popular with asylum seekers from Africa.

Workers’ Kitchens Before the Foundation of Israel

The modern Zionist movement was founded in Eastern Europe, and many of its members belonged to socialist movements which promoted physical labor in agriculture, construction and manufacturing as a crucial means of “fixing” the condition of Jews in the Diaspora. Mostly living off commerce and real estate, Jews in Eastern Europe were accused of being “parasites” exploiting the labor of others. Therefore, manual labor was perceived as a value, and the Hebrew worker, the ideal Zionist figure of the early 20th century, had clear characteristics: a strong, muscular body, simple clothes, a humble abode and belongings.

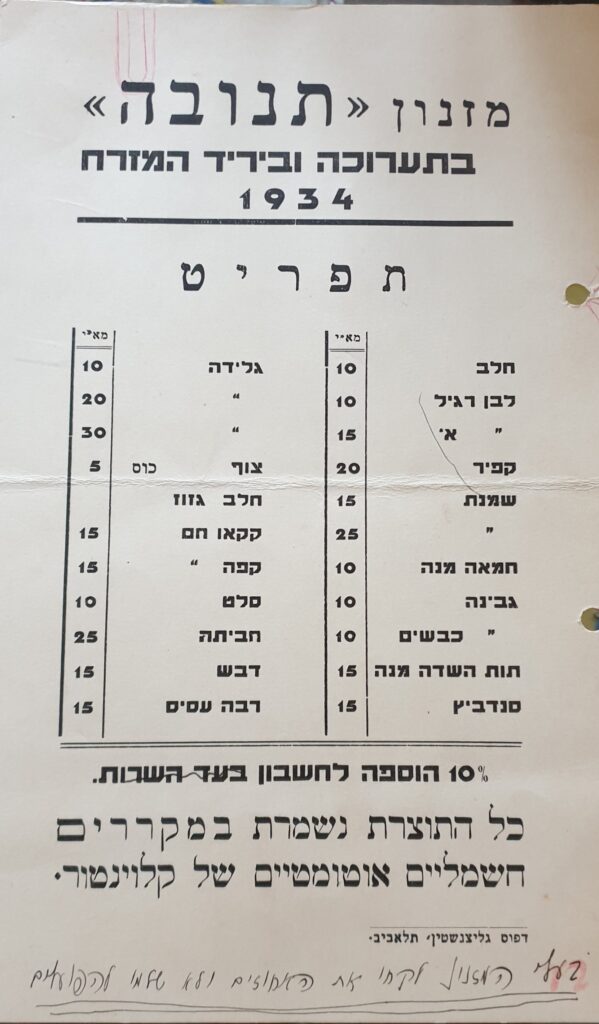

Workers’ kitchens or cooperative restaurants, operated and sponsored by ideological-political movements, were founded to feed these workers. Simple meals were served at a low price or for free to their members. The menu was simple, for a few reasons: members of the Zionist movement scorned (at least officially) bourgeois hedonism, most of the immigrants (“olim”) were young with no culinary training or knowledge of good food, and ingredients and resources were scarce. As most Zionist Jews came from Eastern Europe, the meals were Jewish-Ashkenazi both in content (chicken soup with noodles, casseroles etc.), and in structure (soup, first course, main course, and dessert). The simple and even dull menu, low-quality ingredients and lack of cooking skill are in part responsible for the perception of the Ashkenazi kitchen as bland. It is interesting to note that although the food itself changed in the coming years, the Eastern European structure of the meal was mostly maintained in the institutional, and still subsidized, versions of these restaurants (military canteens, hospitals, and educational institutions).

The immigrants of the fourth and fifth aliyot (in the 1920s and 1930s), and later Holocaust survivors who migrated to Mandatory Palestine, were less ideologically committed, if at all. They contributed to the creation of a bourgeois, urban, Ashkenazi middle class, with more sophisticated culinary preferences. Their initial social marginality, however, eliminated any possible challenge to the supremacy of the socialist ideology and its culinary expressions. The dining halls of the kibbutzim, which were another form of early workers’ restaurants, remained a model for eating in the young, developing society.

The Creation of the Israeli Working Class and the Rise of the Workers’ Restaurant

The mass immigration of the two first decades of Israel’s existence dramatically changed the ethnic and class make-up of Israeli society: it tripled its population, pushed many of the “veteran” immigrants up the occupational stratification ladder, and shaped some of the newcomers, mainly through external circumstances and pressures, into the young country’s working class.

These immigrants came from diverse countries and cultures, with distinct socio-economic, cultural, academic, and professional backgrounds: some of them were Holocaust survivors from Europe, and others, immigrants from North Africa, the Middle East, the Balkans and Romania. Despite fundamental differences between the groups, all of the immigrants from Arab countries were redefined by the state as Mizrachim (or “Oriental” Jews). Within two decades, they developed into a distinct socio-economic class with a common cultural identity and political orientation, challenging and finally replacing the Eastern European political elite. Members of this new group were tracked into manual labor trades, and like the halutzim (pioneers), they needed inexpensive, nutritious food; yet this time no communal kitchens or kibbutz dining halls awaited them. The substitute was workers’ canteens, privately-owned inexpensive restaurants which opened in the geographic and social periphery like Ramla and Lod in the center of the country and Jaffa and the southern part of Tel Aviv, and the so called “development towns” near the borders like Sderot near Gaza and Kiryat Shmona in the far north. These restaurants catered to the culinary preferences of the new immigrants with a limited selection of Mizrahi dishes and cooking methods from their homelands like Moroccan couscous, Kurdish-Iraqi kubbeh and grilled meat, as well as dishes from the Arab and Palestinian kitchens, such as hummus, tahini, and falafel.

Bulgarian and Romanian restaurants popular primarily with workers from there opened in Jaffa and Haifa, yet the relatively rapid integration of these immigrants into the Israeli middle class meant they were perceived as “ethnic restaurants” — not fine dining, but not low-priced workers’ restaurants either.

At the same time, an additional working class was created by the state — Israeli Palestinians. Seen as potential enemies, they were forced to live under a military regime limiting their economic, social and cultural agency and integration into Israeli society. The physical, ideological and religious segregation restricted the few food destinations in Arab villages and towns (mostly falafel stands and hummus places, and sometimes restaurants serving grilled meat and cooked food) to Palestinian manual workers, preventing them from offering their services to the Jewish population. With the end of the military regime in 1966, and the influx of Palestinians from the territories occupied in the 1967 war, Israeli Palestinians were able to move up the socio-economic ladder of Israeli society. The Jewish Israeli market gradually opened to Israeli Palestinian-owned restaurants, yet only in recent years have they managed to gain (limited, but well deserved) recognition. The menus at these restaurants are relatively affordable and reminiscent of, and at times identical to, those at Mizrahi places. They, too, can be categorized as “workers’ restaurants.”

It’s also important to mention the Jews of Yemen here, who were perceived as “natural” manual workers, able to compete with local Arab workers. They were tracked into the economic-occupational-geographic periphery, bringing with them culinary elements which would gradually become cornerstones of the Mizrachi-Israeli kitchen, such as jachnun. They were also probably the first to adopt falafel, an emblematic working-class food, from the Palestinian kitchen, transforming it into a staple of Israel food.

The immigration waves from the USSR in the 1970s and 1990s did not give rise to workers’ restaurants serving Russian food. Similarly to the waves of immigration from the Balkans and Romania, most of the immigrants, mainly of the younger generation, integrated successfully into the Israeli middle class due to their academic background and their identification as “almost Ashkenazi.” The fact that their culinary institutions were not perceived as workers’ restaurants (despite serving generous portions) indicates the significant correlation between ethnicity and social status in Israel. At the same time, immigrants from the Caucasus, some of whom found employment as manual laborers, were treated with the same stereotypes as the Mizrahi Jews. Low-priced Caucasian and Georgian restaurants in the geographic and social periphery were labeled as workers’ restaurants, and adopted elements from Mizrachi and Arab workers’ restaurants, such as serving a selection of salads and bread, hummus, tahini and a kind of hot sauce (harif), as well as Mizrachi-style roasted meat.

Foreign Workers Restaurants

Since the 1990s, the Israeli job market has relied heavily on foreign-born workers: migrant workers from Thailand, China, and Turkey, who arrive legally to work in agriculture and construction, as well as refugees, asylum seekers, and migrant workers with no legal status, most of them African, who work in cleaning, renovation, and gardening in urban areas. While documented migrant workers haven’t opened restaurants or food stalls for workers in their community, African migrant workers and asylum seekers, as well as undocumented workers from East Asia have near Tel Aviv’s Central Bus Station.

Most of the modern-day workers’ canteens in Israel are therefore Eritrean and Filipino. Meanwhile, Palestinian manual workers eat bread, hummus, yogurt and canned food at their place of work. Jewish-owned restaurants catering to Israeli Jewish manual workers can primarily be found at the outskirts of big cities, and sometimes in residential neighborhoods and commercial centers in peripheral cities. While they mostly serve Mizrachi food, their most popular dish is frequently an Israeli fusion: Ashkenazi schnitzel in a pita with hummus, hot sauce (harif), and French fries.

The New Workers

In the 1970s, the North American anthropologist Dean MacCannell coined the term “staged authenticity,” to describe the way the tourism industry creates (and maybe fakes) experiences for tourists. MacCannell found that people that experienced the alienated lifestyle characteristic of the industrialized Global North traveled to remote countries and cultures wishing to experience “authenticity in the lives of others.” European and American residents, for example, who usually purchase packaged rice in the supermarket will travel to Thailand and Vietnam to see farmers plowing with water buffaloes, cutting stalks with a sickle, and threshing the rice in the field. As they enjoy this experience, they ignore the rapid industrialization and modernization process affecting these places and their manufacturing processes. The tourism industry thus organizes performances of authenticity, masquerading as regular human activities.

Staged authenticity is a key factor in the success of modern, trendy and expensive “workers’ restaurants.” These institutions, which once served nutritious food to manual laborers, are now subject to rapid processes of gentrification: the Israeli middle class rushes to restaurants in Jerusalem’s Machaneh Yehuda market, the rebranded Yemenite quarter in Tel Aviv, and the Bulgarian and Romanian restaurants of Jaffa and Haifa. They are looking for an “authentic” experience, which comes with a hefty price tag — as the diners pay for that staged “authentic” experience along with their food.

And one may also claim that Israel’s real contemporary workers’ restaurants are the cafeterias and restaurants of the high-tech hubs. They feed the new, much-needed workers, who are as happy for their lunch cards as their grandfather was for his union member card, that bought him subsidized lunch at a workers’ kitchen.