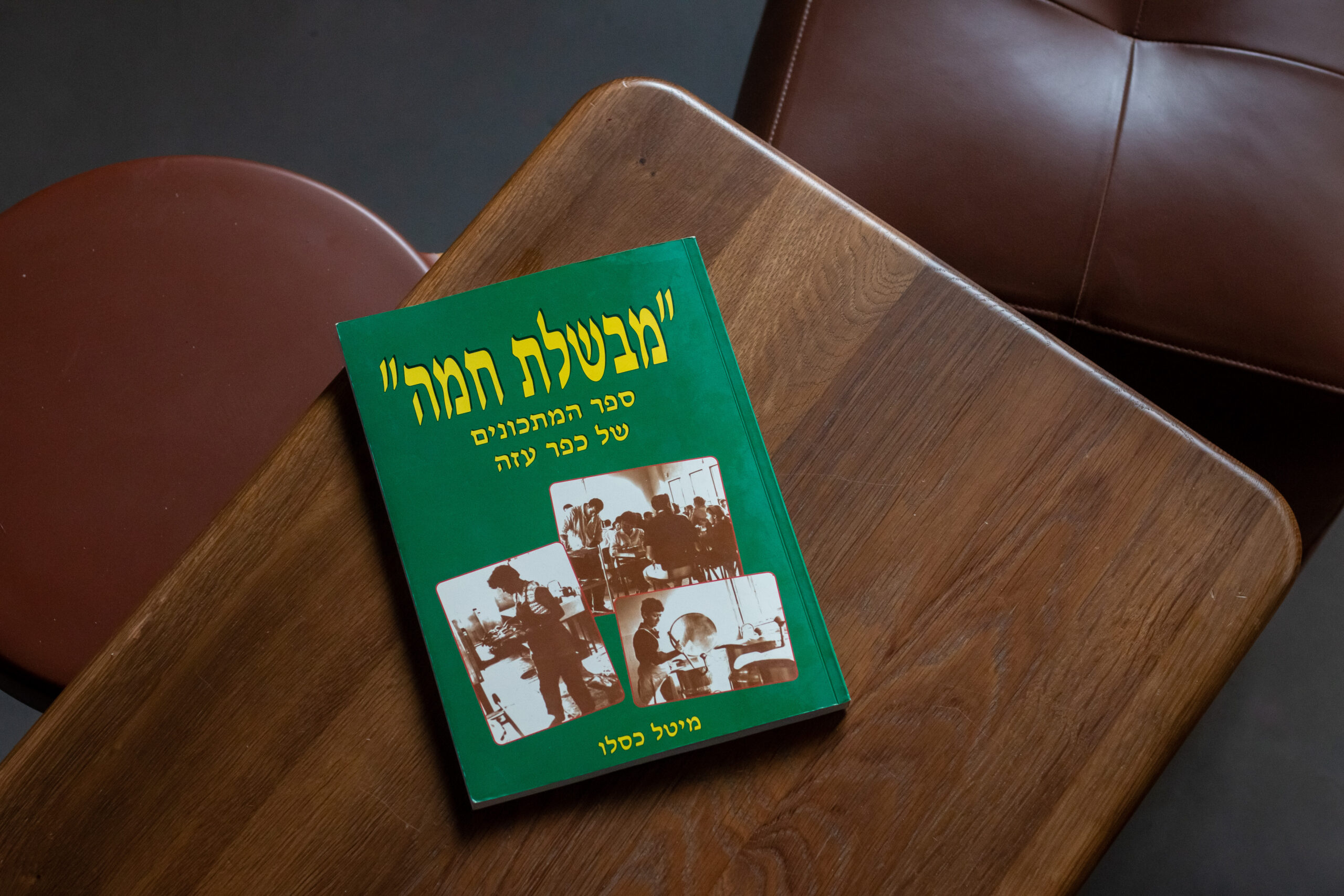

While working to catalog the Asif Library, we stumbled across a treasure: “Mevashelet Hama: the Kfar Aza Cookbook.” A collection of recipes and anecdotes from kibbutz life, this gem is a monument to a beautiful, unique past. Since October 7, it has also become a tragic one.

Located on Route 232, just 2 km east of the Gaza border, kibbutz Kfar Aza was founded in 1951 by two groups of immigrants — one from Egypt, the other from Tangier in Morocco. The first years of the young kibbutz were marked by instability and challenges, finally leading to its temporary abandonment in 1955. Reestablished in 1957, the kibbutz was home to several businesses including Kafrit Industries, the sound company Sincopa, and to one of Israel’s biggest dairy farms. More recently, it was also home to approximately 800 people. On October 7, 2023, armed Hamas terrorists invaded Kfar Aza, murdering 63 people and taking 17 hostage —10 have since been released, two were killed, and five remain in captivity.

“Kibbutz resident Meital Kislev was the spirit behind this book,” explains Adi Shai, the manager of the Kfar Aza archive. “She had been diagnosed with cancer and during treatment, she had to remain isolated at home, but she had the idea of collecting recipes from the people of the kibbutz.” Meital asked neighbors for recipes, scoured the archive for photos of the kibbutz’s kitchen and dining hall, and collected local food-related vocabulary.

The kibbutz provided the funding and the book was published in 2000. “In the beginning, there were only a few copies, but with time the book gained a life of its own: people began to pass it around, to look for recipes, and it became popular among the kibbutz’s families. Meital Kislev died of cancer, and the book remained as a beautiful souvenir,” Adi adds.

“People loved Meital, and they were happy to take part in something that made her happy. And the book really managed to express the spirit of the kibbutz,” says Yael Bogin, a former kibbutz member. “Meital created a wonderful book with many local idiomatic expressions and stories, and it raised everybody’s spirits.” Eti Koren, a resident of Kfar Aza, agrees: “There was something highly optimistic about it all. Meital really put everything into it, and people cooperated, donated their family recipes. We were all enthusiastic.”

The ethnic diversity of the recipes is notable, with delicacies such as Yemenite jachnun, Ashkenazi cholent, North African chraime and matbucha, Hungarian rakott krumpli, and Russian piroshki. “Kfar Aza has always been an international kibbutz,” confirms Adi, contradicting the common perception of kibbutz food as predominantly Ashkenazi and bland.

Communal kibbutz dining halls were affected by their environments as much as they affected it, and unique dishes developed on each kibbutz. In “Communal Dining: Stories and Recipes from the Kibbutz,” by Assi Haim and Ofer Vardi, there is a story about a group from Morocco that started Mimouna festivities (Maghreb Jewish celebration marking the end of Passover) on kibbutz Tze’elim. And on kibbutz Be’eri, Persian immigrants introduced other members to their kitchen. After all, kibbutz members met in the communal dining hall three times a day, influencing each other.

Yael, a member who left the kibbutz a decade ago, explains: “In the first years, cooking on your own was an effort. For years, people didn’t have the means of cooking at home, and in many kibbutzim, baking was only done in the common kitchen after working hours. As a child, I would go with my grandmother to the bakery in her kibbutz, and she would bake everything in the communal oven. On Kfar Aza, we had a miserable stovetop, an electric kettle, and at some point, an oven. We mainly baked cakes. The expansion of the private kitchens happened much later.”

A Kibbutz Vocabulary

When the dining hall is the epicenter of everything, it’s only natural that unique words and terms are coined around it. The popular “Malka Salad,” with cabbage, carrots, mayonnaise, lemon, and sugar, was named after its creator, former Kfar Aza kibbutz member Malka Loria. Another item of local folklore is the “Surprise Egg” dish. Invented in the kibbutz’s first years of hardship, it consists of a hardboiled egg, coated in a dough made from mashed potatoes and flour, which is rolled in breadcrumbs and finally fried.

The book’s title is one of these idiomatic terms as well: Yosef Yosha (known as Yosha) got tired of eating cold sandwiches during work, and asked to receive hot cooked meals. His request was granted and food was heated up by someone the kibbutzniks called “mevashelet chama.” It was later used to describe the person in charge of heating up food for the Shabat meal. Despite having a feminine grammatical gender in Hebrew, the term was used indiscriminately for men and women.

Another unique word on the kibbutz is merucha (a riff on the word mimrah, meaning spread) for a vegetable puree for babies. (“If the little one doesn’t like the merucha, add some sugar, and he’ll gobble it down,” says the book). Ben David eggs, or poached eggs served on special occasions, were also named after a legendary cook on the kibbutz, Amnon Ben David.

He worked in the dining hall for 34 years and contributed a few recipes to the book. He had retired two years before the kibbutz was privatized in the late 1990s. With privatization, home kitchens became bigger and more sophisticated, and people started approaching him with requests for recipes.

“When I was a child, the dining hall still served three meals a day,” remembers Reut Peled, the 33-year-old daughter of Gila and Yizhar Peled, who were murdered during the Kfar Aza massacre. “They stopped serving breakfasts in the 1990s. Dinners continued for a while, creating childhood experiences well beyond food. Each evening involved exciting planning, and the key question was: who to sit next to?” Privatization, she says, changed the communal kitchen, too. “In the past, kitchen workers were people from the kibbutz, but at some point, they were replaced by outside workers.”

When people started opening cookbooks, they were exposed to new flavors and cooking methods, and the inventory at the kibbutz grocery store changed accordingly. “There was no longer just milk, biscuits, and bullion cubes, suddenly we had a whole shelf of products from the Far East, and some new, exotic spices. Kibbutz members started asking for specific products,” Reut adds.

This shift was felt in the Peled family home. “When we were kids, cooking at home was kept to a minimum — light dinners, pasta, pashtidot. Our Yemenite grandmother would make Yemenite soup for lunch on Fridays, and we had jachnun on Shabbat. We only began making Friday dinners with kiddush at home when the communal dining hall became less active. That was also the time we started doing more substantial cooking. My parents did not grow up on the kibbutz, and when they lost the privilege of the dining hall, they returned to their roots, to the food of their mothers.”

Gila Peled’s Jachnun

Gila Peled (59), her husband, retired Brigadier General Yizhar Peled (62), and their son Daniel Peled (28) were murdered on October 7 in their home in Kfar Aza. Gila and Yizhar had three other children, as well as grandchildren, who all live on the kibbutz.

Gila’s daughter, Reut, recounts: “When we were kids, my mother always made jachnun. Everyone in the kibbutz knew the Peled family always had jachnun for Shabbat morning. Our cousins would arrive and mom would open the pot and take a plate to the lucky neighbor of the week. The recipe in the book uses margarine, but she would sometimes replace it with samneh, a clarified butter prepared by her mother-in-law. Mom refused to make samneh herself; she said it made the entire house and the curtains stink.”

“Growing up, our home revolved around food — its center was the dining table, surrounded by memories. It was a home that focused on the good, on recognizing the good in life, and even when things got rough, you moved on. Clearly, this is much harder to implement right now, but we do continue to repeat this mantra, because it’s really rooted in us, much more than we had realized,” Reut shares.

The Peleds started the Dandis Candies project, an Instagram page dedicated to the memory of Yizhar, Gila, and Daniel, who always wondered why people served bourekas instead of gummy candies at shivas. A bowl of colorful candy was placed at the family shiva, and people continue to tag similar bowls in his memory.

Tami Peleg Ziv’s Spritz Cookies

Tami Peleg Ziv (72) lost her brother, Nimrod Greenberg, on October 18, 1973. It was Simchat Torah. On October 7, 2004, also Simchat Torah, her daughter, Einat Naor, was murdered in a terrorist attack in Sinai. And 19 years later, on October 7, 2023, Simchat Torah, Tami and her partner, Eitan Ziv (74), a tour guide, were murdered in their home.

The voice of Asif Peled, Tami’s son, is filled with emotion as he describes his mother’s baking. “Mom was an extraordinary baker. She baked for many years, but only went to study baking professionally at a relatively late age. The old kibbutz had a member’s club and when the weather was nice, they would meet on the lawn after dinner for coffee and cake. Mom baked many of these cakes.”

This tradition is documented in the Kfar Aza cookbook: “There was a time [when] the member’s club was the meeting place of the social people of the kibbutz. It had newspapers and magazines from all over the world, board games, laid back conversations, and most importantly, Tami Peled’s wonderful cakes, which were a good enough excuse to visit.”

Asif says his mother was famous for classic, simple cakes. “Her signature cake was her babka. I bake myself, but no matter how many times I asked her for the recipe, or how closely I watched her make it, it was never the same. She used to make this insane cheesecake garnished with whipped cream and plenty of berries. I spent a lot of time in the kitchen with her as a kid, and sometimes also as an adult. I don’t know if I’m being nostalgic here, but I’ve tasted many desserts and talked to many bakers, and most cakes don’t even come close.”

Reut and Asif admit that some of the cookbook’s recipes are outdated. “They all have margarine and bullion cubes in them,” says Reut with a smile. “Mom had stopped making these recipes when everybody started eating healthy,” Asif explains. “I loved mom’s spritz cookies so much when I was a kid. I would eat them by the dozens. You cannot publish a recipe like that today — it’s a 1980s thing, when margarine wasn’t yet taboo. But they were the very definition of home.”

“It’s a funny book,” Reut sums up. “Mom and my partner and I were going through it not long ago, and we laughed so much. Ridiculous recipes like antipasti: cut vegetables and bake them with olive oil.”

The ingredients, explains Yael, were simply a sign of the times. “Margarine was one of the groceries distributed to kibbutz members, that’s why it’s in the recipes. Nobody uses it anymore. But I think the book is still relevant. Would I buy it for a young couple? I’m not sure, it’s really for the people of Kfar Aza and their families.”

Eti agrees: “The book is still relevant. It gave Meital so much, and made people communicate with each other. If I didn’t understand something in one of the recipes, I would go ask the writer. It made me connect with people in a positive way, and I was really proud of the result. I loved looking at this book.”

“The Essence of the Place”

Many kibbutzniks with no cooking knowledge found the book to be a blessing. “I remember I saw it in the store, and I immediately grabbed a copy. I was so proud we had this local cookbook that captured our kibbutz. I loved knowing that people cooked these recipes on Fridays,” says Eti. “I’m not especially keen on cooking, but I loved using it — it helped me a lot. There’s Danny Stallman’s Irish bread, for example — Danny is a friend of ours, and we used to make this bread for years, we loved it so much. Our children still make it. Or Orly Regev’s olive snacks — we baked them with the children at our kindergarten. Or Tami Peleg’s cakes — I dreamt of being able to bake like her. It never happened, and each time I scolded her: ‘Tami, what did you leave out?’ The only recipe that always worked for me was Hagit Yosha’s cold pasta salad.”

“The book was always on my shelf, and it felt like a personal souvenir from my mother,” says Noy Kislev, Meital’s daughter. “And suddenly I realized it also belonged to the community. That it made everybody remember Kfar Aza, the essence of the place, the optimistic days of the kibbutz. Especially now, when so many people from Kfar Aza are far away from their kitchens, and do not even know when they will get back. And some don’t even have a kitchen to go back to.” She and Dror Bogin, Yael’s son, have decided to publish a digital version of the book. “Maybe later we could open it up and add more recipes,” she says. “It’s really not just Meital Kislev’s book, but something a bit bigger — the story of a community.”

Research: Yoni Dagan, Aya Zlotnikov.