This question may seem simple: a “workers’ restaurant” is a common term in Israel, conjuring up associations of cozy, simple dishes, pots brimming with food made from inexpensive ingredients; a place designed to provide quick and satisfying meals to working people during the day.

However, if we break this emotionally-loaded term into its two components, “workers” and “restaurant,” more questions and contradictions arise. Isn’t a restaurant a place of leisure? Do blue-collar workers have time to spend at a restaurant in the middle of their workday? Are we talking about the Hebrew workers, who worked with their hands to build modern-day Israel? Do such workers still exist? If so, who are they?

Journalist and researcher Israel Sher explains that three main parameters distinguish workers’ restaurants: “They are open for lunch and usually closed during the afternoon and evening; as this is the most important meal of the day, the customers sit down to eat, unlike in fast food-restaurants or stands, where one eats ‘on the go;’ and most of them serve an organized meal on a plate, consisting of a portion of animal protein and a changing side dish or stew from pots of homestyle food that are cooked in advance.”

Not a Workers’ Restaurant; a Workers’ Meal

If you ask chef Haim Cohen—whose father was a construction worker when Haim was growing up in the 1960s—workers’ restaurants feeding actual workers have never existed since workers don’t take a break to eat in a restaurant in the middle of the day. As a child, Cohen sometimes accompanied his father at construction sites. He remembers how they went to the nearest grocery store to get what he calls “a workers’ meal” — white bread, leben or cheese, and olives; sometimes they added hard-boiled eggs from home. “The real workers I knew would bring food with them that they, or their wives, prepared in advance,” Cohen explains.

Anthropologist Dr. Azri Amram who researched Arab and Jewish relations in food spaces in Kfar Qasim, a town west of Tel Aviv, says residents have told him workers’ restaurants weren’t a major part of the local culture. “People who worked in the area came home to eat. Others took their lunch with them, or a relative would bring them food in the middle of the day,” Amram says. “Workers’ restaurants appeared to feed those who could not return home. One of the reasons street food developed so rapidly is because most people no longer work close to home. They leave the village to work in the big city, and they need to eat something during the day. Street food stalls usually answer this need.”

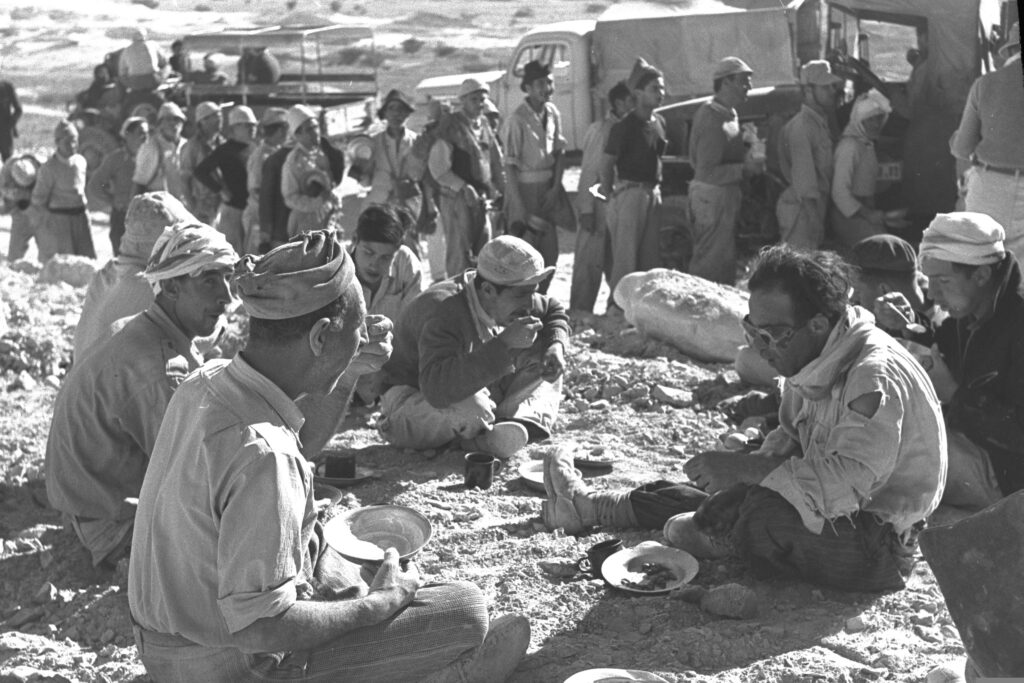

Chef Nashat Abbas, a founder of El Babor and the owner of Sahara Palace, remembers that in the 1970s and 1980s construction and agriculture workers from Kfar Kanna, an Arab town in the Galilee, took food with them when they left for work. “The custom was that each worker brought his own food,” he says. “They would sit down in a circle, and each one would place his food in the middle, and they would all eat together. Today, a large percentage of the Arab population works outside, women too, so we eat out more.”

Homestyle Eating, Away from Home

“Today, when we are talking about workers’ restaurants, we are really talking about inexpensive restaurants,” Cohen emphasizes. “The word ‘workers’ denotes the cheap prices and the type of experience, or its lack of one — it’s not a place to spend two hours relishing your meal. You eat and go. This is the birthplace of phrases like ‘eat, don’t chew.’ The word ‘workers’ is highly misleading because it’s not a restaurant for actual blue collar-workers. Of course, these workers still exist, for example Chinese construction workers, but you won’t see them at a workers’ restaurant [these workers] cook their own food or bring it from home.”

Amram adds: “The intention behind these restaurants was to enable you to eat the food you eat at home even when you are far away. In Kafr Qasim I saw a construction company that employed hundreds of Turkish workers. They all came with cooks — from each village, a cook who could prepare the familiar food of their home.”

Abbas also remembers the workers’ restaurant his family opened in Jaffa in 1983, where he started his culinary career at 17. Every morning they served hummus, ful, mshawashe (chickpeas with tahini, lemon, and olive oil) and omelets with plenty of herbs. By lunchtime the pots were filled with stews such as Hungarian goulash, Palestinian maftoul, and North African chraime, so that each customer could find their own dish, their home food. “I remember an onslaught of people in certain hours, usually between 10 and 11 in the morning, and you had to work quickly and prepare in advance to be able to feed all these people in such a short time. I think a chef who starts his career in a workers’ restaurant will know how to cope with stress. You learn all you need to know,” he says.

In the Hatikva neighborhood of Tel Aviv, Amram says older residents remember two building supply stores that operated until the end of the 1990s — and workers’ restaurants that opened nearby to feed their customers. “Each morning at about 5 a.m. the workers would arrive with horses and carriages, and later in pickup trucks. While building materials were loaded into the vehicles, the workers would sit down to have breakfast. It usually included a hearty soup to keep them full throughout the day. To this day, this part of the neighborhood is famous for its soup restaurants, like Carmela Soups and Boaz Soups. The skewers joints and other restaurants came later, but it all began with the need to provide those workers a hot meal.”

Journalist Amit Aaronson grew up in Jerusalem in the 1990s and his father, an architect, used to take him to have lunch in the legendary Chen Restaurant when he went to work with him. There, they would run into all the contractors and city hall clerks. “They didn’t have a cafeteria, so this was a substitute. All around the city’s center, between Zion Square, Safra Square, and City Hall, there were many small restaurants like Pinati, Taami, or Hamoshava restaurant on Emek Refa’im Street, which all served similar food — hummus, kubbeh, meatballs, rice and beans, and a stew or a schnitzel; there were always pita and pickles on the table. This wasn’t upscale home food, like at Azura — just simple, inexpensive food. Another thing they had in common was the informal atmosphere — a welcoming place to go back to, which serves as a substitute for a home meal,” he says. “What defines a worker’s restaurant, is not the customers but the food. Manual laborers do not take a break from the assembly line and construction site to sit down at a restaurant. The customers are more middle-class clerks than working people.”

The main goal of these restaurants, explains Sher, is to feed their customers — as simple as that. “Workers’ restaurants have an unwritten agreement with their customers: they provide satisfying meals at reasonable prices. The sensation of being full is crucial, and this is why most of them serve bread and other side dishes, such as pickles, a salad or a spread on the house. Some restaurants make additional gestures. In Tel Aviv’s Yemenite Quarter, for instance, owners walk around with a pot of hot soup, offering a refill to those who are still hungry or want more soup, free of charge.”

From a Workers’ Dish to a Business Lunch

“Looking back, it seems workers’ restaurants are a metamorphosis of market restaurants,” Abbas says, referring to restaurants in and near shuks or semi-outdoor markets like Jerusalem’s Machane Yehuda. These restaurants utilized the fresh produce from the shuk to feed the market’s vendors. He adds: “Workers’ restaurants began appearing when industrial zones were formed. With the development of the high-tech industry, these restaurants adapted and created a business lunch menu to attract the new crowd.”

Amram also agrees that the business lunch menu (an affordable pre-fixe) is an updated version of a workers’ restaurant: “It doesn’t matter if we are talking about high-tech workers eating a 120 NIS menu, or other workers having a ‘workers’ meal’ that fit their budgets. If we assume there are no more Hebrew manual laborers, the business lunch menu makes it possible for workers to leave the office, eat a meal with an appetizer, main course, and possibly something to drink at a fixed price, and then return to work. This is a contemporary workers’ restaurant service.”

Chef Avivit Priel Avichai, whose restaurant Ouzeria, lies at the heart of the Levinsky Market, believes workers’ restaurants cannot exist today. “Nowadays, operating a restaurant is a very expensive business, which makes it almost impossible to sell a cheap meal. The Persian restaurants of the Levinsky Market were originally workers’ restaurants, but changed along with the market itself. At Hanan Margilan, which is a chef favorite, you come in the middle of the day without planning ahead, eat your dushpera [Bukharian meat-filled dumplings] and go back to work. But is it accessible to workers? A blue-collar worker cannot afford to eat there. Just those of certain social strata, and even for those who can afford it, it’s probably not every day.”

Aaronson agrees that the decline of workers’ restaurants is related to the soaring cost of living: “Today, even simple clerks don’t make enough to eat in a restaurant at the center of Jerusalem. There are more places selling food in a baguette or a pita, and fewer people sitting down to eat something on a plate. The difference between a pita and a plate can be 20 NIS, which makes a big difference if you eat out every day. The clerks have been replaced by high-tech employees, but these restaurants now serve a different kind of food. Even business lunch menus have almost disappeared. The simplest meal today would cost about the same as an expensive business lunch before the pandemic. Azura in Tel Aviv, for example, has become the unofficial cafeteria of bank managers. Regular folks cannot afford a meal at 150 NIS per person on a daily basis. The essence remained the same, but it’s the price that makes the difference. Those who can afford to eat out every day are high-tech workers, or well-off lawyers and managers. Even in industrial areas like Talpiot [in Jerusalem], you hardly see traditional restaurants; it’s mostly places selling schnitzel in a pita. It’s hard to find people who eat kubbeh for lunch, and if they do, they’ll pay quite a bit for it.”

Cultural researcher Dr. Dafna Hirsch concludes: “If you think of a restaurant as a place of leisure, the term ‘workers’ restaurant’ may indeed sound like a contradiction. If in a chef’s restaurant there is a focus on food aesthetics, in a ‘workers’ restaurant,’ at least the way it is usually portrayed, functionality has the upper hand. Food is seen as fuel for the ‘human engine.’ It’s a place where manual workers can get nutritious and cheap food, so that they can continue working. Such a concept of food was established at the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, when nutritionists, politicians, and sometimes industrialists joined together to promote the idea of rational nutrition — that is, dietary patterns with the most effective ratio between price and nutritional value, aiming to let workers reproduce themselves [as if they were machines] and thus maintain industrial peace. But the term ‘workers’ restaurant’ also carries more romantic associations, related to the discourse of authenticity. In this context, they are seen as ‘authentic,’ simple and unpretentious institutions, in which ‘authentic’ people eat homemade, tasty and filling food at a low price.”