It must have been divine intervention by the gods of the market that during the shiva for Ezra “Azura” Shrefler — the longtime owner of the iconic Azura restaurant — I met Reuven Abergel, a co-founder and leader of the Israeli Black Panthers, a movement that fought for justice for Jews from Arab countries. Born in Morocco, Abergel arrived in Jerusalem with his family in 1950 where they were housed in abandoned mansions of East Jerusalem’s former aristocracy that were perforated by the bullets of the Arab Legion.

At the shiva, consolers came and went, and Abergel praised Azura for his extraordinary generosity. Born in Diyarbakir in Eastern Turkey, his family left for Israel in 1948 to escape anti-Jewish riots. Ezra was 13 at the time and the eldest son. When the family reached Jerusalem, he had to work to help support them. He started as a dishwasher at a small place in the market in 1954, when Rahamim Ben-Yosef opened Rachmo next to a truck drivers’ drop-off point, he hired young Azura to cook. Drivers and porters started their day with his homemade hummus.

Workers of the Market Unite

After 1948, the Machane Yehuda market and the neighborhood attracted an influx of immigrants from Arab countries. It wasn’t considered a place of leisure, and there were hardly any places to sit for a meal. “People cooked at home and came to the market with a pot, making rounds between the stalls,” selling food to the vendors, says Abergel. His father had a grocery store in Musrara, but for him and his brothers, the market provided a sense of belonging. “Unlike the Ashkenazi neighborhoods, where they saw us and immediately thought we were trouble,” he says, and continues to express anger with Arab Jews who fail to recognize themselves in Palestinian children.

The cooks would place the food on the stalls and leave without disturbing the merchants’ work. “Each one ate the food he knew from his mother’s house, and nobody stole, and nobody cheated. The cooks knew they would get paid, if not today, then tomorrow, if not this week, then the next. And if they forgot, the merchants would remind them,” he adds.

Over the years, the flavors of the different immigrant kitchens, those from Moroccan, Kurdish, Persian, and Syrian cooks melded with the Sephardi flavors of the Old City. And, as the walls between East and West Jerusalem’s markets came down, the taste of the pot continued to evolve.

When Azura struck out on his own, he also carried pots between stalls and hamaras (drinking holes). Finally, he opened his first restaurant in the Mamila neighborhood in the 1950s. “Azura worked harder than four people combined,” Abergel says. “By 6:30 a.m., he would already be making his rounds with his homemade food, at worker-accessible prices.”

Abergel misses Azura’s food, and the kubbeh hemo sold by the Doga brothers, who had owned a market stall back in Baghdad. Flat, large, yellowish kubbehs, called taklitim (vinyls) because of their shape. You can still hear the joy in his voice as he describes the fat and juicy meat, the kubbeh shell cracking between one’s teeth, and the moment the hunger dissipates after hours of carrying heavy loads around the market.

“Life was so hard; it was almost unbearable,” says Abergel as he describes the central role gambling and drinking played. He remembers the cards and dice in the market’s card rooms, the clubs (pronounced: cloobs), and the alcohol beckoning at the hamaras, where the market workers, cooks, cleaners and porters would stop on their way home to have a drink and a bite, while fellow vendors Nino and Morris Bitton played and sang songs by Abdel Wahab. They came to let the alcohol wash away the day’s hardships and their longing for a lost homeland, and to let the music massage their muscles. The kitchen born in these hamaras served the best food in the city.

“Some hamaras were for bums and others were more upscale,” say Azura’s sons, who operate two restaurants under their father’s name in the Iraqi market in Machane Yehuda. The pots of sofrito and oxtail stews, or kubbeh soups, simmering over kerosene stoves seem to connect the market of the past and its present form, where a false sense of authenticity is sold at cafes and stores with words like “baladi” and “asli” (authentic).

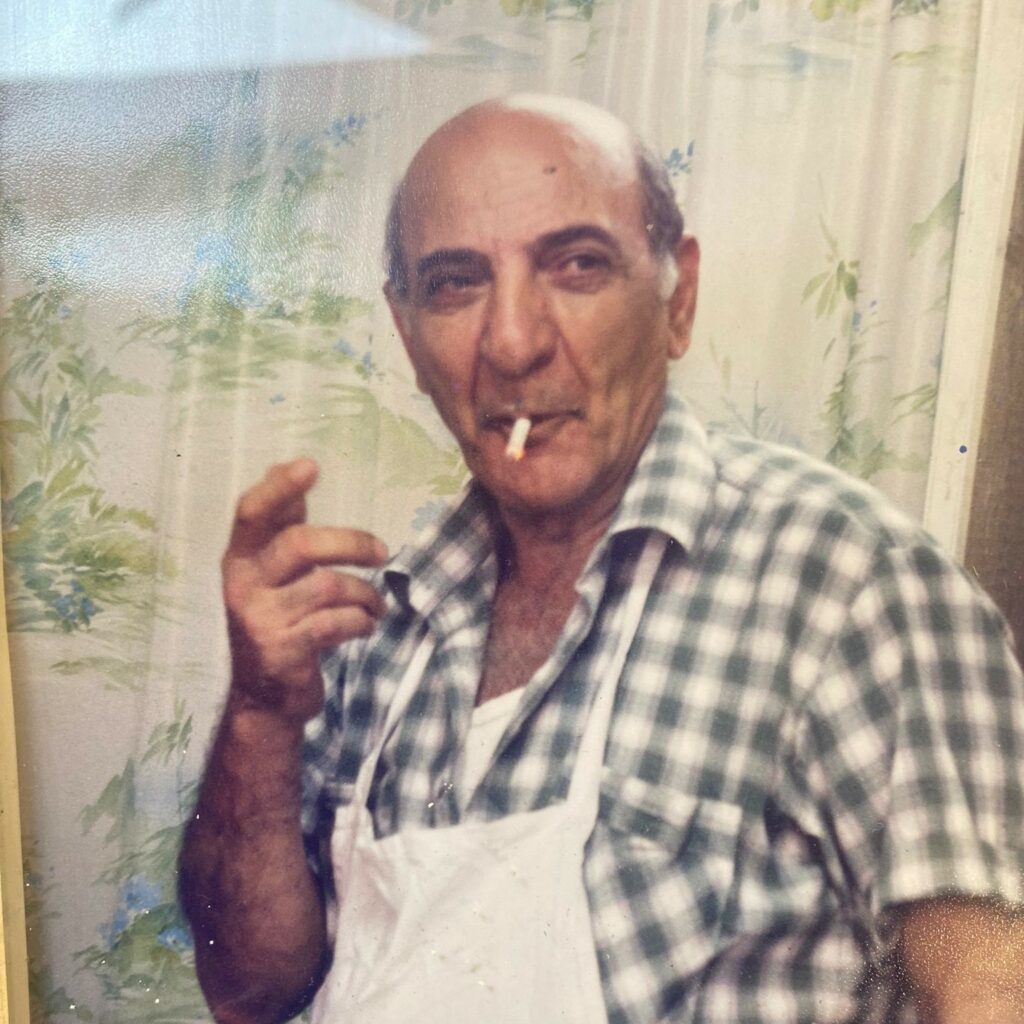

Their father used to close shop around 4 p.m., they recall, to go play cards and then drink — he was particular about where and with whom he drank. The market, everyone knew, had drinkers who ordered cheap arak drinkers and those who ordered top shelf alcohol like their father who always drank whiskey, with an eternal cigarette between his fingers.

“The Tastiest Theater on Earth”

“Having to choose between hamaras and crime, I chose hamaras,” says Pini Levy of the iconic and now shuttered spot At Pini’s Yard, who was a pioneer of the Jerusalem kitchen that grew out of the market. “University wasn’t part of our vocabulary back then.” The middle child of seven siblings, he was born in the Jerusalem neighborhood Nachlaot three months before the 1948 war to a family of butchers, who emigrated from Yemen at the end of the 19th century. When he was five years old, his family moved to a house overlooking the shacks and stalls on Agripas street; the market was his playground.

The heat of Jerusalem’s summers made everyone at the market thirsty. Workers and shoppers used to stand in line at the cart that sold drinks like tamarind juice and rozata (orgeat). And Pini remembers the kebab sold by Eliyahu Glan, who was always thirsty. “He moved from cart to market stall with the power of thirst,” Pini says smiling.

For years, Pini had the keys to all the market’s butcher shops. He would get there first thing in the morning to cut the meat for them, and by noon, when he was done, he would go sit in one of the hamaras, bringing a few chunks of meat to place on the charcoal grill — a must-have at any place that wished to attract the market’s drinkers.

“Sometimes the owner announced there would be beef head or leg of lamb stew the next day. In most cases, it was the market people who brought the mezze,” says Pini in that quiet voice of his, which knows how to recount Jerusalem so beautifully. His memories recreate one big workers’ restaurant, to which fishmongers brought sardines or red mullets, butchers were responsible for meat, nut vendor contributed sunflowers seeds or lupini beans, and pickle sellers brought mackerel wrapped in a newspaper, which they would set on fire and leave until the paper burnt down to reveal a poor man’s smoked mackerel.

There was also the vendor who sold sabras or cactus fruit, who brought green chickpeas in season, which he roasted in one of the bakeries. “Hamala malan,” he would say, or “full term pregnancy,” to let everyone know his pods were full. He used to drink outside, without mixing with the others. Slaughterhouse owners also used the ovens of the market’s bakeries to bake their special pots called siniyas, with fillings like offal, plenty of fried onions, vegetables and herbs, that were eaten at the hamaras with esh tanur, which is what you call a taboon bread in Jerusalem.

“It was best with some fat from a heifer’s udders,” Pini continues as he takes us into the minutiae of a disappearing world, in which a poor man’s moral dictated that if you took an animal’s life, you must consume it in its entirety. When I asked if there were also vegetarian options, he responds: “Are you crazy? If someone didn’t eat meat, everyone thought he was sick.”

Pini says it was the tastiest theater on earth: a man known as Berdugo the Sephardi walked around dressed in a 3-piece suit with a pocket watch, but without teeth, chewing a butcher’s steak with his gums. The Persian woman who plucked chicken, would step into one of the hamaras every time she felt like having a drink, holding her cheek to show how bad her teeth hurt. No one believed her, but they would pour her plenty of arak anyway, for her cheek and effort.

And there was the pickle guy who had a glass eye, and left it in his glass every time he went to the bathroom to make sure no one touched his drink. Alcohol’s that way. Nothing beats alcohol when it comes to fueling distrust or inflaming political debates, which were part of the hamara’s soundtrack way before the market became an obligatory stop for modern election campaigns.

“Nobody had any idea what he was talking about, but drinking gave it legitimacy, so nobody made a fuss,” Pini laughs, and then grows serious. “Alcohol is silent as long as it’s in the bottle. When it goes to your head, you figure out what noise it can make, what scandal it can cause. Someone raising his glass above someone else’s was enough for a Third World War to break. There was some fighting — things would get a little physical, and then they would come down.” Then, as if wishing to breathe into the thought, he adds: “It was their world, and everyone felt very macho: the Persian, the Syrians, the Iraqis, the Kurds, the Moroccans. Outside of the market, it was a different story.”

Respectable women were not part of this world. Wives almost never came to disturb their husbands’ drinking routine at the hamaras. Let them do what they want, as long as they put bread on the table at the end of the day, was the thinking. If you ever saw married couples fighting, it was in the clubs, when women came to drag their husbands home before they lost all their earnings on dice or cards.

“These men, even if they were starving, they wouldn’t leave the table,” Pini laughs. “The food had to come to them.”

Longings for a Home Across the Wall

The Doga brothers made their rounds between the clubs with a pot wrapped in several blankets. They served kubbeh Hemo on pieces of paper with some radishes and hot peppers, way before chef Eyal Shani turned this serving method to his trademark. “I burned so much money in those clubs,” says Morris Bitton, one of the greatest musicians and meat experts ever to come out of the market.

I met him in the spring of 2001, a time of unceasing terrorist attacks. He had his own hamara on HaAgas street in a tiny room that had once belonged to the famous Banai family of actors and musicians. The market people brought chunks of meat or fish, and he roasted them on a small charcoal grill according to each one’s individual preference, adding some charred vegetables and a freshly chopped salad – each customer had his favorite salad, which he knew by heart. The only thing that could compete with his culinary talent was his singing.

But even he surrendered to the transformations that swept the market under the late Eli Mizrahi, a third-generation vendor and as sweet a person as they come, who was responsible for converting the market into a late-night scene.

In 2006, Morris moved to one of Jerusalem’s main streets: together with his son, he opened a “real” restaurant, right by the butcher shop called Zikwe the Georgian. It had a large grill, chairs and tables for customers, and Morris, who never committed to a single butcher, went meat shopping every morning, surveying the market with piercing eyes, judging every piece from a distance.

On Thursday nights, or whenever he felt like it, he would play and sing, with his younger brother Nino or without him; to an audience, or just to himself and to Azura, who would sit and listen, a cigarette between his fingers and whiskey in his glass. For a moment, as he is telling me this story, I can see the child he once was. Now he cooks in a small place his son opened next to the Russian Compound frequented by lawyers.

On the few occasions I heard him sing I wanted time to freeze. I wanted the music emanating from his mouth to go on forever. I wished the fingers pulling the cords of his mandolin would never stop, nor would those of Nino, one of the best oud players Jerusalem has ever seen.

They grew up in a house where friends would gather at the end of each day to listen to their father play and sing. His father was a famous tailor in Morocco and while he never lived off his music, he would perform at celebrations if someone couldn’t afford to hire musicians.

He didn’t teach his children a single note. Each time a hafla (party) started, he would send them to their room, but they listened and learned. “If father were alive, he would own half the market,” says Morris. “We came to Jerusalem in 1956, and it took everybody one second to realize what an extraordinary tailor he was.” But he passed away at 52, before he had a chance to see what musicians were brewing in his house, behind the door.

When they started to play hamaras, Morris was 14 and Nino 12. They began in their older brother Lalu’s place, and continued to other people’s hamaras. They would never leave them, even when music took them to the most prestigious ensembles, to the biggest venues.

Then came the shock of 1967. After being told for years about the enemy lurking in East Jerusalem, the Six-Day War came, the fences fell, and Jews who had come from Arab countries realized the food and music of their Arab neighbors reminded them of the homes they still longed for.

Clubs with dual, Jewish and Arabic, ownership opened in Jerusalem. Morris and Nino played there with musicians from Jenin, Bethlehem, Ramallah, and Nablus. They no longer had to go to Noach Café in the Tikva market in Tel Aviv to find immigrants who were some of the greatest musicians of the Arab world. Now everybody came to their own places.

Abergel says the authorities got scared, and began spreading rumors that they were pimping Jewish girls to Arabs. The bars closed down, leaving behind a memory of music, a feeling of frustration and a heartburn for missed opportunity.

Offal for Breakfast

It could have been a coincidence, or an inspiration from the breakfast of the residents of Old Jerusalem – a pita filled with beef and mutton offal cooked overnight. Either way, it’s a fact that the Jerusalem mixed grill wasn’t invented before 1967. The dish was born in the steakhouse that Haim Piro and Gideon Amiga opened on the market’s fringes and would become an object of city pride.

The story goes that a man enters, asks what there is to eat, and Piro throws some chicken liver, hearts and spleens on the grill, together with beef kidneys, calf hearts, some tomatoes, some onions, and a basic seasoning of salt and black pepper. The vendors on Agripas street followed the lead and adapted it, filling pita with chicken offal.

Then, when the American fast food chain Wimpy came to town in the 1960s, Jerusalem started roasting offal on an electric stove. The variety of meat decreased, the quantity of spices used increased as did the number of people claiming to have intended the dish.

Battles are still raging, thanks to the storytellers who lead tourists around the market. There’s no trace of Piro and Amiga’s original mixed grill, and all the more for the siniya — a dish glorifying the long-gone days when food was mostly cooked for the market’s workers, in an enclave that felt misunderstood by the outside world. These people went to great lengths to feed one another within their world. Or as Pini puts it, everybody came from food, everybody worked hard; for them, cooking well was a matter of honor.

Today, tourists and shoppers fill the market’s cafes and restaurants. The Ministry of Health banned the small grills every vendor had once operated wherever and whenever they felt like it, and you can no longer burn fish wrapped in a newspaper in the middle of the sidewalk. The market has been renovated, and you won’t see any vendors sitting on the floor to pluck chickens or shell peas. Still, the flavor capsule born in the market between the 1950s and the end of the 1990s lives on, both in Israel and in the world. You can see it in the kitchen of the Machneyuda group and in that of Eyal Shani; it’s there when chef Ezra Kedem cooks for the rich and famous; it lives on in Rafi Cohen’s kitchen, and also in Ibn Ezra, the Turkish restaurant Elran Shrefler, a gifted cook and Azura’s youngest son, has opened in Tel Aviv.

Hila Alpert’s fascination with food moves within the culinary traditions and cultures in which she grew up. It travels in time, wishing to simmer at the roots. A prominent Israeli culinary figure, Alpert is a writer, food maker, journalist, lecturer, TV host, cookbook and restaurant guide writer, and a consultant to restaurants and the food industry.