Scenes in dining halls, taverns, and cafes abound in Hebrew literature and music, but despite Israel’s socialist past, workers’ restaurants make surprisingly few appearances. It takes some time to trace them and analyze their role and meaning.

The “Hebrew” worker — the idealistic Zionist who had once wished “to build [the country] and be built” — is on the verge of extinction. As more Israelis have moved into white collar jobs, Chinese, Thai, Palestinian, and Filipino workers have stepped in. Today, these are the hard workers who pave local roads, dig subway tunnels, work long days in the fields, and tenderly care for the elderly. In the cultural consciousness (and in the literary field), the workers’ restaurant of today is probably located on the Neve Sha’anan pedestrian street or in the Asian market of Tel Aviv’s Central Station.

Still, the myth of the classic, idealized “workers’ restaurant” of the past — with its outdated decor, familiar dishes (“with a modern twist,” as they like to say on reality shows), generous portions, “authentic” atmosphere and relatively-accessible prices — keeps growing. Some of these restaurants take advantage of this trend and put an almost vulgar emphasis on the nostalgic working-class ethos: the Facebook page of the famed Azura in Jerusalem’s Machane Yehuda market promises “nostalgic stews cooked on kerosene stoves,” and displays close-up photos of giant simmering pots. Literature and music is also recruited for brand-building purposes, with Yossi Banai’s well-known song welcoming the guests: “If it is a graceful day of spring/ and my heart is so thirsty that it gasps/ I go to Machane Yehuda market/ and sit down at Azura’s place…”

Yet all this mythmaking cannot hide the simple fact that the very core of these places is missing — the workers themselves. Manual laborers no longer take their lunch break at Azura or other places like it — they wouldn’t be able to pay the bill. “The idea that a worker can work from 8 a.m. to noon, take an hour-long break to go eat at a restaurant or even at a shawarma stand, and then go back to work seems inconceivable, a waste of time and money, even out of line,” says Daniel Monterescu, professor of urban anthropology and food studies at the Central European University in Vienna. “We should also remember that a meal in what is now considered a workers’ restaurant is far from cheap. Workers who build roads, work in construction or in agriculture will settle for a basic meal of bread and cheese or salami and some olives on the side to cut costs.”

Is this transformation reflected in Hebrew literature? And if yes, through which perspective? Let’s start with an examination of Shabtai Teveth’s “Ugat HaTapuchim Shel Ima” (“Mother’ Apple Pie”), included in “Sipurim Me’Etmol” (“Stories of Yesterday”), a collection of short stories dedicated to his magical childhood in Tel Aviv of the 1930s. Shifra, his mother, does wonders in the kitchen, and her food, notably her apple pie, inspires admiration and joy in family members and guests. Two houses down the street, Mrs. Schecter, a significantly less gifted cook, serves a home-made lunch to residents of the neighborhood — a teller at the Kupat Holim (a medical clinic), the cashier of the old-fashioned grocery store, the union dues collector, and others. With very little enthusiasm, they eat her carrot salad, mashed potatoes and the watered-down fruit compote she serves every day at precisely the same time, and pay by punching holes in pre-paid cards.

Shifra is envious of Mrs. Schecter, and decides to open a restaurant for just one day — the first pop-up restaurant, if you like. With dishes like Egyptian eggplant salad, veal in Yugoslavian sauce, and the famous apple pie for dessert, the restaurant is a great success; there is also dancing and music. But the next day, a small-scale uproar arises as the disappointed guests discover it was a one-time thing.

Workers’ restaurants started just like that, recounts journalist and author Nathan Dunevich in his 2012 “Mi-kiosk Gazoz ad Misedet Shef — Mea Shnot Ochel be-Tel Aviv” (“From a Soda Kiosk to a Chef’s Restaurant — 100 Years of Food in Tel Aviv”). In the 1920s, families in need of extra income welcomed regular guests to their family table, for a fee. “They served whatever was cooked that day. Soup, a main course with side dishes, a dessert. Guests paid in cash or put the meal on their account,” writes Dunevich. The same thing happened in Jerusalem’s Mishkenot neighborhood, testifies author and researcher of the Old Yishuv Yaakov Yehoshua. In his 1971 book “Shekhunot bi-Yerushalayim ha-yeshanah mesaprot: pirḳe hoṿe mi-yamim ʻavru” (“Stories from the Neighborhoods of Old Jerusalem: Contemporary Chronicles of Days Gone By”), he writes about a woman named Bracha Yitzhak, who served affordably-priced food to workers and to the poor. “It was the first workers’ restaurant,” he claims.

In addition to family-owned institutions, small inexpensive restaurants began opening up, starting in the 1930s, writes Dunevich. The first appeared in Derech Yafo in Tel Aviv, then on Herzl street, and in other areas in the developing city and beyond. “For a minimal fee, guests received a bowl of hearty bean soup and a thick slice of brown bread. And a bottle of tap water, free of charge.”

Workers’ kitchens began appearing in the 1940s, allowing workers and their families to fill their stomachs for a nominal fee. With time, they evolved into successful cooperative restaurants run by Zionist organizations, feeding masses of people. The most famous of these institutions was Beit Brener in Tel Aviv, which served about 2500-3000 meals a day until falling out of favor in the late 1960s. A typical menu included dishes such as Russian eggs (hard-boiled egg in a mayonnaise dressing), a soup of the day, meatballs with two side dishes, and a fruit compote for dessert. Punch cards were stamped as payment.

As this short and incomplete survey shows us, the workers’ restaurant was never a homogenous creature, but rather a mosaic of distinct restaurants with some common characteristics. This is well expressed in Eli Amir’s 2018 book “Na’ar Ha-Ofnayim” (“The Bicycle Boy”). The book’s protagonist, 16-year-old Nuri Halashi, immigrates from Baghdad to post-1948 Jerusalem on his own, wanting to get an education and save his family from a life of poverty. Food is present on almost every page of the book, as his life as an errand and newspaper boy on a bike is intertwined with Jerusalem’s multiple workers’ restaurants.

Since Nuri was short on cash, he ate lunch at Trabelus, a “cheap, poorly lit” restaurant on King George street. Mr. Trabelus, “a bald, stocky Jew” sat at the entrance with his gloomy-eyed, lanky son. “The crowd at this inexpensive restaurant was comprised of workers, passerby, and working youth,” describes Nuri. “The fixed menu included soup, a cube of fried beef tenderloin, a mound of mashed potatoes, a mound of peas, and a bowl of yellowish jelly for dessert.”

When he didn’t eat at Trabelus, he would go to the cooperative restaurant on HaPoalim street, where one would eat “cholent, a small plate of cabbage salad, some pudding and sweet challah — exquisite delicacies.” Both restaurants offered workers a filling, unpretentious meal at an accessible price. They were far removed from the bourgeois Hesse restaurant with “sounds of music emanating from below,” or Café Hermon in the Rehavia neighborhood, where Nuri is taken by Michal, a girl from a higher class — and appalled to discover he could not pay for the espresso and strudel she had ordered.

“The purpose of these restaurants was to provide the worker high-energy food that cost less than the energy his body produces,” explains Dr. Yahil Zaban, a professor of Hebrew literature at Tel Aviv University and author of “Eretz Okhelet: Al Hate’avon Hayisraeli” (English title: “A Land of Milk and Hummus: A Study of Israeli Culinary Culture”). “So this was a cheap, nourishing meal. Usually, these were also considered generous restaurants, the kind that use large plates and offer a refill.” Workers’ restaurants were mostly open for lunch, during the working day, says Zaban, adding: “customers usually communicated directly with the owner — and this is something that’s remained, because it expresses a fantasy of returning to simplicity, a longing for something that is more authentic, in interpersonal relationships, too.”

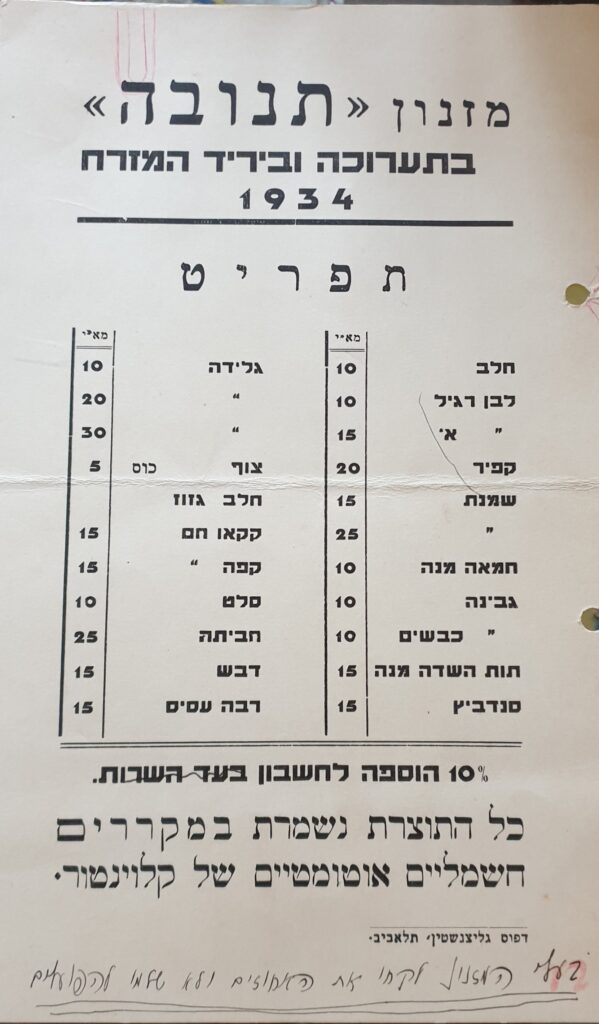

Nathan Alterman 1965’s song “Zemer Mapuchit” (“Harmonica Song”) is a clear manifestation of this longing: “In San Francisco, Marseille and San Malo / There may be inns, pubs and taverns / With women of all colors… / It really isn’t hard to find a lover / But despite all of these, I swear / My heart is given to a shabby Tnuva.” Ready to give up on the luxury and charms of the big wide world, in return for the simplicity, stability and informal, home-like atmosphere of a Tnuva canteen. These canteens first opened in Jerusalem in the 1920s, later expanding to Tel Aviv, and were famous for their dairy tzena (austerity) meals, served by waiters clad in white aprons.

Such informality was also typical of the relationship between restaurant customers and owners. While Alterman swears loyalty to a restaurant, Meir Ariel dedicates his “Etzel Tzion” (At Tzion’s Place; from the 1997 album Bernard & Louise) to Tzion, the owner of his favorite joint. Their relationship is more reminiscent of that between a son and a loving parent, than that of a customer and a profit-driven business owner. The song goes “At Tzion’s Place, on the corner of HaYarkon and Trumpeldor/ Between the post office and Cinema Dan / you get a lot of heart in your pita / for a little more than a dime / you get a lot of love in your pita / for less than a quarter of time / At Zion’s they only care about satisfying / the customer’s wish / and so it’s a pleasure to come here / hungry, thirsty and beat/ before you order he offers/ doesn’t let you wait one bit.”

“‘Etzel Tzion’ reveals additional characteristics of workers’ restaurants,” says Zaban. “The first thing we learn is that a workers’ restaurant is connected to the street, to a certain neighborhood, to a certain area. The people who eat there are locals. It has a local vibe — if it’s in Florentin, it has a piece of Florentin; if it’s in Ashdod, it has some of Ashdod in it. The customers have a sense of belonging.”

The Restaurant’s Location Is Part of Its Identity

“A workers’ restaurant has a unique, individual character; it’s not a copy-and-paste thing. And this applies to the owner, too — it’s not a franchised business. It is usually family-owned. The owners are around, and their character and permanent presence are meaningful…. You’re eating in their place,” Zaban adds.

The perception of the workers’ restaurant as a substitute for a home is reflected in literature. This is particularly true for men and all the more so for those without a “home.” It is no wonder that author Batya Gur’s mythological, forlorn detective Michael Ohayon, eats at a workers’ restaurant. In the 1989 “Mavet BaChug LeSifrut” (English title: “Literary Death”), Ohayon, recently divorced and a father of one, is striving to solve a double murder mystery. He goes for lunch at Meir, a workers’ restaurant in Jerusalem’s Machane Yehuda market: “The only place to go to enjoy oneself, for a little break, after discovering a body, after tensions at work, after witnessing a pathological examination.” Meir has typical characteristics of the genre: it’s “authentic” (with photos of politicians and famous rabbis), generous (a wide selection of salads is served before the skewers and kebabs), and it’s family-operated (the three young cooks-cum-waiters-cum-cashiers treat Ohayon “with exceptional courtesy and respect”). But most importantly, “Meir was the only source of light in this area of ghostly darkness.”

The protagonist of A. B. Yehoshua’s best novel “Five Seasons,” Molkho is an accountant and recent widower, who finds himself sitting in a workers’ restaurant on a strange venture to the Indian town of Zira, during a failed attempt to find the town’s treasurer. It isn’t his local restaurant; on the contrary: he is drawn to the sensation of foreignness, plus the feeling that his late wife would never set foot in such a place. As a form of rebellion, he sits down and orders an offal stew. The sensation of home is nearly unheimlich: the Indian cook somehow knows that his wife had died, consoling him as if he were a local. And the food, which he consumes with alarming passion, has “a deep concise scent, like his father’ sweat.” After the meal he feels weak, “as if the meat he ate drew him close to the ground,” and falls into deep sleep in the bed of the Indian girl who showed him around the town.

All of these examples portray the workers’ restaurant as a stable haven in an unstable reality, as a sturdy home, immune to the vicissitudes of the protagonists’ lives. But despite that, these very same examples show traces of significant changes in the nature and role of workers’ restaurants in the 20th century, a consequence of social, political and cultural transformations.

Monterescu points out two intertwined, significant changes: “A workers’ restaurant is in its essence a class-related definition of a lifestyle: urban, popular and cooperative, or family-centered,” he says. “Yet this lifestyle, just like the institutions and organizations which made it possible, no longer exists.” It is another process in the fragmentation of Israeli identity: you must brand yourself in terms of identity politics to gain power in the society. Successful categories are family-related: a Tripolitan, Moroccan, Tunisian mother/grandmother, and so on. Authenticity, claims Monterescu, has been ethnicized. “The workers’ restaurant, originally a class-related social structure, has become an experience of ‘authenticity’ marked in ethnic terms.”

As workers’ restaurants distanced themselves from the class values or political thinking that inspired them, a process of ethnicization was made possible and set into motion. “Workers’ restaurants are part of the Zionist history of the Israeli Labor Party,” says Monterescu. “This movement has exhausted its historical role; the set of values it promoted is fading away, and the same goes for the Hebrew worker. Therefore, the restaurants which fed these workers are no longer needed. What remained is a simulacrum, an image cut off from its roots.”

And once an image is cut off from its roots, it’s easier to commercialize, I say to Monterescu. He responds: “The image of the workers’ restaurant has indeed been subject to commercialization, which is reflected on several levels. Instead of a fixed menu including an appetizer, a main course and a dessert at an accessible price, we have individually priced, expensive dishes. Instead of authenticity, we have an allegedly-authentic experience of commercial simplicity, ‘genuineness’ in a plate, or in short, ethnicity. And in present-day Israel, ethnicity is Mizrachi, because the Israeli consumer perceives Mizrachi as authentic.”

A Disentanglement and Loss of Meaning

Monteresco adds: “This, too, is a result of our postmodern age. Workers’ restaurants no longer serve workers’ food, as much as they offer an imaginary grandmother, who is really nobody’s grandmother. They serve what we like to call ‘comfort food.’ I think it validates in-depth processes in the entire Israeli society: in the past, it was perceived as a melting pot, but today, Israeli society is trapped in an ever intensifying [era of] identity politics. People are looking for fixed identities, and this is the reason the workers’ restaurant is replaced by ethnic food. It is no longer a restaurant for workers, but it still reflects the ethos of comfort and family atmosphere, or at least a longing for it. Quite an expensive longing, one must say.”

“Workers’ restaurants still serve workers’ food, like meatballs and beans,” Hebrew literature professor Zaban reiterates. “Even the strictly Ashkenazi schnitzel is eaten today in every Mizrachi restaurant in Israel. But it is served to the bourgeoisie. It is an interesting ironic inversion, in which bourgeois high-tech workers, who are practically glued to their office chairs, eat food meant for people who do physical work. That is, these restaurants serve bourgeois customers the recompense and prerequisite for hard physical labor, without them having to work for it. In that sense, the middle class appropriates the working class’s identity, thus preventing it from rising up against them.”

Furthermore, in the Israeli consciousness, Ashkenazi identity is no longer associated with ideas like comfort and family, adds Monterescu. “Ashkenazi food had been a cornerstone of these restaurants, and as a child, I frequently ate at Tiv Restaurant on Allenby street, where they served customers red cabbage, goose legs, and a bowl of beans or soup. But today it seems inconceivable, both culturally and commercially, that a workers’ restaurant would serve Ashkenazi food. P’tcha simply isn’t comfort food.”

Dunevich also links the gradual decline of workers’ restaurants starting in the late 1960s to the fact that “the city is brimming with inexpensive restaurants, mainly Mizrachi ones. Young people, but not only them, chose Mizrachi.” In the 1970s, author Amos Keinan wrote an elegy to cooperative restaurants in general, and to Beit Brener in particular, in his Yediot Aharonot column: “The same Beit Brener, but no longer a buzzing hub of public life, but a cemetery for memories.” According to Keinan, “the young workers movement is dead.”

The Ashkenazi workers’ restaurants are replaced by Mizrachi restaurants, skewer spots, hummus places, and falafel stands. Diners struggling to adapt to the change can be spotted in writing even earlier. In Ephraim Kishon’s 1955 Maariv column “Shishlik, Sum-Sum, and Zifzif,” (“Shashlik, Sesame, and Zifzif”) he humorously writes that his stomach “remains the same helpless foreign stomach, a Hungarian nationalistic creature.” It has a hard time adjusting to the menu at Ovadia’s canteen, next to his office, with its Mizrachi dishes and their “funny spices.”

Kishon recoils from the extravagant portions and unfamiliar names, which he deliberately distorts, writing things like “couscousul” instead of couscous and describing dishes that “reek of sulfuric acid” or have “a drop of sandpaper powder.” It’s easy to label his comments as racist today, but it is clear Kishon views the owner Ovadia with his blatantly belittling smile and his spicy, pungent cooking as a manifestation of a new Israeli masculinity; his failure to digest the Mizrachi dishes, whose “flavor was infinitely foreign to my soul,” was a failure to pass this masculinity test.

Most of the workers’ restaurants we see in the following years are inexpensive spots serving Mizrachi food. Menachem Talmi’s 1971 “Tmunot Ya’foiyot” (“Jaffa Pictures”), which tells the story of a Jaffa gang, opens with a feast at the iconic hummus spot Abu Hassan (half a dozen mezze, two large groupers, a pile of barbecue ribs, arak, beer and whiskey). In Dudu Busi’s 2003 “Pere Atzil” (“Nobel Savage”), Eli, a sensitive boy from a tough neighborhood who suffers from an eating disorder, is torn between his mother, a recovering drug addict, and his father, an unconventional artist. The novel describes Eli’s visits to his favorite restaurant, Musas’s place. There, he orders a skewer of foie gras, taboon breads, and salads, devouring them on the spot with “giant, nervous bites” exposing his eating disorder — in other words, he feels at home. In the 1990 book “Ahavat David” (English title: “The Second Book of David”), Yoram Kaniuk recounts a tale of a fictional Minister of Defense during the 1967 War, a controversial larger-than-life character; a kind of contemporary King David, a great, charismatic and revered soldier, but at the same time also uninhibited and lacking morals. His photograph on the wall of a local falafel stand encapsulates the dual attitude towards him. These are, of course, but a few examples.

Yet it seems Hebrew literature has so far failed to acknowledge a current, fascinating transformation: the new customers of these old school workers’ restaurants. “The classic proletariat was replaced by high-tech workers and the precariat — the precarious class, consisting of temporary workers, refugees, students, and artists — disadvantaged workers lacking a secure workplace,” says Monterescu. “[Most] Israelis no longer work in construction; they write code, or manage the precariat that builds for them — and go to eat at a workers’ restaurant, a pleasure they do not allow these new workers.”

Still Looking For a Nostalgic Fix

The customers have changed, the DNA of these restaurants has also changed, but we still go to these places to feel at home, to get a fix of nostalgia, looking for some intimacy in our estranged urban environment. “With the estrangement and alienation of capitalist life, these culinary institutions provide a substitution for a lost sense of community, a recompense to our rapid pace of life, to taking frozen meat out of the freezer. Because in the end, we are looking for comfort,” Monterescu adds. “Maybe we are also ashamed of turning our backs on the constitutive ethos of ‘a society of workers’ and the ‘conquest of labor.’ Maybe it’s also nostalgia for a reality which disintegrates before our very eyes.”

Israeli literature likes to use culinary metaphors in discussing the national state of affairs, but you won’t find a description of the disintegration of the working class through the commercialization and ethnicization of workers’ restaurants. Monterescu’s descriptions of “imagined authenticity” and “grandma on a plate” are tinged with considerable irony, while contemporary literary portrayals of hummus places and inexpensive restaurants lack any trace of irony, malice, or criticism.

Yet, there’s one short story that seems well ahead of its time in its description of the disengagement of the workers’ restaurant from its fundamental values. In Yehoshua Kenaz’s 2008 book “HaTik HaShahor” (“The Black Bag”), a father and a son go to eat hummus; most of the customers sit outside, but the father decides to step inside. We soon find out that the parents are divorced, and that the child lives with his mother. The father doesn’t know what his son likes to order; in fact, he doesn’t know that he doesn’t like hummus at all.

After ordering two plates of hummus with chickpeas, hard-boiled eggs, pine nuts, tahini and even beef, he returns to his newspaper. He talks on the phone — probably with a woman, without noticing that his son has no appetite, isn’t feeling well, and that he is terrified of Erez, who had been involved in a brutal fight and now sits and eats his pita at the next table. The father finishes his food and walks out, leaving his son to finish the unwanted food. “In the end, food is a form of communication and attachment,” says Zaban. “Without them, it is just bland.”

The sick child doesn’t make it home; his temples pounding with pain, he throws up as he reaches the front yard. The notion of a hummus place as a family restaurant is exposed as an empty shell. An onlooker may see a father and son absorbed in a ritual of Israeli masculinity and family — sharing a plate of hummus to bridge the gaps between them, but this gap only grows wider and deeper. The intimacy and solidarity are, at most, longing for something long gone, if it ever existed.

The current discussion of workers’ restaurants carries a certain degree of irony and sadness over what has been lost, yet we can find some consolation in the fact that the approach to food continues in the domestic sphere. “Workers’ restaurants may have disappeared from the urban landscape, or [have been] redesigned and priced to fit high-tech workers equipped with meal cards, but many homes preserve the simple meals of the past,” Zaban reminds us. “Children eat workers’ food for lunch — schnitzel, rice and mashed potatoes; people still have bread with jam for breakfast, and in the evening, a meal of salad and an omelet marks the end of the day.”

Neta Halpein, started her career as a journalist in The City and Akabar Ha’ir, and wrote about the environment, culture, and literature. At the same time, she taught philosophy and urban studies at the Ron Verdi school for the gifted. She has a masters in literature from Tel Aviv University. Currently, she writes for the family section of Haaretz along with cultural articles and literary reviews. She lives in Tel Aviv.